In March 2011, an earthquake off the coast of Japan caused a tsunami which contributed to what would become the most significant nuclear incident since Chernobyl. The radioactive isotopes released in the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant incident led the government to evacuate over 165,000 people, some of whom are still not able to return. Some villages have reopened and their residents are slowly returning, navigating a new somewhat precarious way of living.

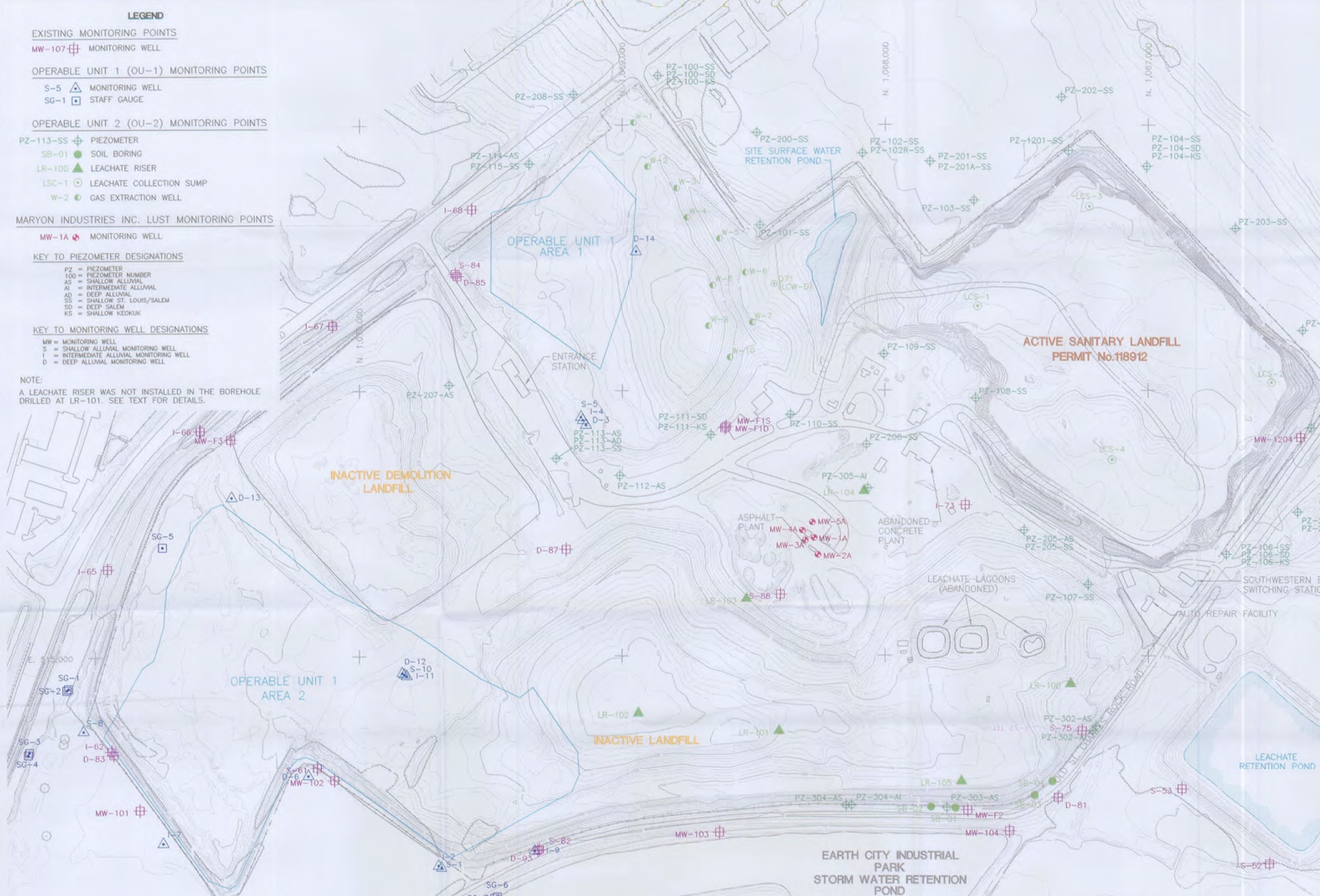

A farmer from a formerly evacuated village shows me fern scrolls we collected from the mountains near his reopened farm. They are precarious because it is not possible to determine how contaminated they are without monitoring them. The local authorities discourage residents from foraging in the mountains and forests because they remain to the greater extent, un-decontaminated. Despite this, the farmer and I, plus around 30 scientists and their families, go hunting for local delicacies in the mountains on their weekend off. Later-on that day, the vegetables are taken to be monitored in a local food monitoring station to confirm if they are above the allowed limit - 100 Becquerels per kilogram. Vegetables within the limit are made into tasty tempura. The rest go to ‘science’.

During a weekend learning farm skills in a formerly evacuated village in Fukushima, we foraged for a host of wild vegetables (sansai). Those that we found were labelled and sent to the local food monitoring station. One bag of our bounty, Koshiabura shoots, exceeded the government standard for most foods: 100Bq/Kg.

The image shows a typical printout from the food monitoring station. The printout shows the detection level of the measuring device - in this case, 42Bq/Kg for Cesium 137 and 67.9Bq/Kg for Cesium 134. It then shows that the combined amount of Cesium in the sample is 737.7Bq/Kg, seven times the allowable limit, if we wanted to sell it. But we were scientists on our day off, we could choose to eat more than the government standard. Afterall, it is just one bag of greens. In the end, the scientists opted to go for the government limit. This sample did not get eaten at our weekend farming party but was instead taken by one of the scientists present back to their lab for further testing.

On another visit to a reopened village in Fukushima, Nakamura-san, a scientist and member of a local citizen science monitoring group, takes me to see the Soil Museum, an unassuming shelter made of plastic covering scaffolding poles. It looks akin to the various flower polytunnels that have cropped up all over the area, in between abandoned paddy fields. The Soil Museum sits in a corner of one such paddy field, close to both a contaminated waste storage facility, a ziggurat of black bags and also a newly erected solar farm, part of the village’s attempt to remove the need for external sources of energy.

The museum does not contain much. Upon looking inside I am faced with a small ditch and a cut out in the soil below, providing me with a cross section of the soil in the field to a depth of about a metre. Grass and weeds sprout at the surface. The top 10cm layer of soil has been removed and replaced, according to government decontamination methods, with alternative ‘clean’ soil, harvested from a mountain elsewhere in the prefecture. The clean material is coarse and clearly a different make-up to the original paddy field soil. I am told not only is the soil not as fertile as what was there before, but also that heavy machinery used during removal of the top layer often crush the underground clay pipe systems that allow the fields to be flooded and drained. Outside the museum, examples of broken pipes lie quietly, unacknowledged inside the repository.

In May 2019 I accompanied three scientists from a Japanese research institute on a visit to a somewhat counterintuitively named ‘wild mountain vegetable’ farm in a reopened village in Fukushima. They are trying to determine why there are large variations in plant contamination across the farm. This place is on the border of farm-land and forest. It is both forest and farm, but at the same time neither one nor the other. When asked whether the plants are farmed or wild, the owner, Hirono-San admits ‘well, they are really wild, but I if I say wild I cannot sell them! So I say farmed.’ Her grandfather planted some of the garlic plants decades ago and they have since spread. Who is to say where the border between wild and not wild is?

Decontaminating it is not so easy because of the terrain. Takahashi-San and I strain to see Ito and Watanabe struggle up the slippery slope to monitor plants in the tree-lined forest. ‘We are scientist hunting!’ he smiles.

An area next to a small river is relatively cleared of trees and has been decontaminated. Hirono-San negotiated with the government to only take off the top layer of soil off. Instead of taking off 10cm as they would do in paddy fields or flatter agricultural fields, they just scraped off the top 5cm. ‘We knew that it did not need to be decontaminated as much.’ How did you know? I ask. ‘Of course we know! Through the history and knowledge we know! These plants only have short roots.’

Velu told me that he had seen people with different instruments probe the water to measure its levels of toxicity. “But they never enter the water. Why don’t they just ask us fishermen? After all, only by entering the water do we make an income.”

The industrialization of Velu’s landscape has heavily affected the river that supports his income. The presence of copper, zinc and mercury has been confirmed by different scientific tests that were designed to measure the levels of bioaccumulation that aquatic life in the river had endured. But Velu knows that the water is polluted. His body, he insisted, was enough to make sense of it.

In the image above, Velu and Surya are drawing the nets they had set up in the river, back onto the boat. Both the action of setting up the nets and the work needed to draw them back on the boat demands the body to be fully or partially immersed in the water. His feet traverse the riverbed, making calculations of its depth and consistency. His body measures the strength of the current as he sets up the nets to withstand its force. His hands work through the nets in the water, untangling any unnecessary accretion that might hamper the proper functioning of his nets. All routine calculations of their river and all measured by their body.

At first glance this image might just appear as two men in the process of fishing. But I wish to reorient our reading of the image. This image is also a representation of the body’s intimacy with toxicity. Not solely as victims of industrial pollution, but also as “embodied empiricists” in their own landscape. Knowing that the water is polluted changes our perspective of the two men. But it is in knowing that both Velu and Surya are well aware of the water’s pollution, through its influence on their body and in their place, can we visualize what we otherwise might believe only lies beneath the surface.

After drawing the nets on to the boat, Velu and Surya sort out their catch. Small prawns form one cluster, the few tiger prawns another, while the rest of the catch is released back in the water. The process of segregation is a long and tedious one. Once complete, Velu and Surya transfer each pile in to different baskets, storing them in an icebox at the very end. They both sigh in relief and rest their backs to the sides of the boat, finally looking out into the distance as opposed to the floor of their boat.

“It used to be scary before the companies came… forests all around… you could even hear jackals at night. I used to get really scared but now… you can see for yourself… this is what happens when the companies come”.

Velu tells me this with his eyes fixed on the power plant in the distance. We see the plant puff away flushes of steam from its stacks, illuminating a once “scary” place with its hyper visible presence. But can we envision its absence? It is precisely this, thinking of the same place without a power plant, without chimneys puffing steam, without incandescent lights setting dark skies on fire, without mercury in the water and in the fish, without the mechanized sounds of energy infrastructures mingling through the day and night, without the smells of an industrial intruder, without “toxicity”, that Velu remembers vividly. This sensorial transformation of place, from jackals to smoke stacks, is where toxicity becomes visible. While this experience is intimate and is a memory that is located in certain bodies, thinking through the absence of ‘toxicity’ in the image above, might help the viewer rethink what is actually there.

After the nets are drawn on to the boat, Velu and Surya keenly inspect them, ensuring that all of the catch falls to the floor, and that there isn't much damage to them. Most often there isn't anything beyond a few frayed ends that would easily be mended the next day. But the nets tell another story that remind the fishers of their toxic landscape. Caked in the residues of the coal-fired thermal power plants that surround them, the once blue nets have incresingly accomodated the greys and blacks of coal dust and slurry. "They look dull now" was Velu's way of telling me that there is something else, in the air, in the water, in his body and his nets, that could be measured by the senses. The material life of things that ineract with the lives of fishers, are equally places were toxicity becomes visible.

Towards the end, Velu and Surya pile the catch together and store it in an ice box. Depending on the size of their catch, fishers choose to sell the shrimp and prawns at the smaller local market or the central fish market that attracts consumers that buy in larger quantities. However, both Velu and Surya insisted that the size of their catch had significantly reduced since the construction of the power plants. This coupled with an increasingly silted river that suffered from numeorus infrastructures that impeded its tidal rhythym only aggrevated their concerns for their landscape. But when a study suggested that the industrial discharge that was let in to the river had accumulated in to the life of their catch, the headman of the fishing village insisted that the reports were false. "We eat what comes out of the river and nothing happens to us", he said proudly, and assured that the same would be true for me. While toxicity makes itself visible to the fishers in this landscape, it is selectively rendered invisible as well. The boundaries of visible and invisble toxicity, though porous, suggests a complex politics of measure that traverse the daily lives of human and non-human actors in a toxic place. I intend for this image to be read in that light. Can we look at it and ask ourselves where the entangled boundaries of toxicity end?

Air's flows are never imagined in a vaccuum. Air pollution always moves from a polluting source (stationary or mobile) to a cleaner source. They become lenses through which developmentality operates, becoming inseparable from geopolitics.

Delhi's air has many spatial valences: neighborhood, urban, regional, national, even transnational. And even as toxics complicate scale, they become known as equalizers.The right for clean air becomes an individual right, a human right, even though advocates know it is a matter of social justice. Why is it so hard for advocates in Delhi to visualize air as a shared yet fragmented experience? What hinders solidarity while acknowledging differences of exposure? What visualisation strategies can be helpful?

I think that one way to disrupt the toxic air-as-equalizer narrative is to simply show that it does regard borders. Not fully, but the way people have to live in, and the way polluting entities become concentrated, makes breathing at the borders precarious. Nor do borders mesh with political borders. They can be frontiers of capital and infrastructure, the borders between our bodies, the borders between our home and the world beyond.

I created this map using two sources: a 2014 report on Delhi's toxic hotspots by the non-government organisation Toxics Link and a 2013 scientific peer-reviewed article by Sarath Guttikunda and Giuseppe Calori. I made the underlying map of Delhi using Google Maps and marked the toxic hotspots indicated by the 2014 report. Then I overlaid the GIS image created by Guttikunda and Calori on Delhi's map, zoomed out to match with the GIS image approximately. There is slight incorrespondence between the two images, mainly because of a lack of technical skill. Despite that, I think the image (both found and created) shows that there are clearly toxic hotspots and clusters near Delhi's actual political borders (marked in red).

A demand for cleaner air has to be attentive to such spatial injustices, particularly as polluting sources have been placed at the peripheries in earlier moments to "decongest" Delhi by moving its polluting factories and workers elsewhere.

In 2018, a "giant pair of lungs" was installed in front of the busy Sir Ganga Ram Hospital in north Delhi. Installed in early winter just before the Hindu festival of Diwali when people would burst banned firecrackers, the lungs are actually huge HEPA filters which are supposed to turn progressively darker one day after another by filtering out particulate matter. And they did, as this time-lapse video shows. By November 8, one day after Diwali, the lungs had turned completely black. This installation was created by Lung Care Foundation, an NGO headed by a prominent respiratory surgeon who lives in Delhi. Two decades before, similar images had circulated when another prominent surgeon contrasted the black lung of a Delhi resident he had operated on with the pink lung of someone who lives in a mountainous area. This installation, though, by using HEPA filters, recenters the materiality of PM2.5 in its connection with the lung. The attachment to Delhi still remains but the attention has shited elsewhere. Emma Garnett writes about the "elemental ambiguity of PM2.5" (2018), the difficulty of grappling with toxicity that is not molecular and that configures scientific research in new ways, demanding new links to be made, new boundaries to be drawn between body/not-body, human/nonhuman, indoor/outdoor. Since the installation locates air within the lungs, it also centers the individual human body as the site for intervention. How does this shape environmental activism and justice?

Though many images of this installation/experiment are available online, I chose this image because of two reasons: it is taken from a right-wing media outlet, and it frames the lungs in relation to a colonial-era war monument engulfed by seasonal smog and bounded by police barricades. The monument India Gate in the background was built in 1921 to honor British Indian Army soldiers who died defending British imperial centers across the world in the First World War. It is significant that the media outlet chose this framing. What toxic histories and legacies does this framing draw attention to and why?

I took this screenshot from Berkeley Earth's Air Quality Real-time Map. The map can be zoomed-in and zoomed-out. So I had to choose the framing of my screenshot. I did not want to choose a flat, connected world though that would tell the story of a global air. I did not want to zoom-in only to Delhi or only to India though that would surely tell the story of urban air or national air. I chose a framing that scientific papers use to tell the story of a world mapped on an axis of progress. In this map, Delhi can be discerned only by a cluster of blue dots (which represent surface monitoring stations) in north India. The map shows that air flows but is contoured by concrete geographies. It presents in full view the different scales that would be confronted by environmental governance: transnational, national, regional, urban, rural. The data comes from surface monitoring stations which means the map also represents highly local dynamics. Visualising air this way troubles scale.

I took this screenshot from an interview of India's environment minister Dr. Harsh Vardhan. The interview's headline expresses the inability of a government which prides itself on conducting "surgical strikes" (covert operations across national borders to kill suspected terrorists) to think the same way about air. I took this screenshot when the environment minister talked expressed a wish that he had a cure for pollution. We see him confront limits of his government's style of functioning. When contrasted with military vocabularies, what does this way of wishing about air reveal about how air is to be managed?

An imagined technoscientific infrastructure comes home. On the lines of China, Delhi might get anti-smog tower", reads a news article from The Times of India in November 2019, promising an infrastructure of purification that should work in Delhi because it works in Xi'an. The actual smog tower inaugurated in January 2020 is painted in the Indian tricolor of saffron, white and green, inaugurated by cricketer turned politician Gautam Gambhir who represents the political party BJP in the constituency of East Delhi. BJP is the political party that currently forms the central government of India, galvanizing people on communal polarisation and ethnocentric nationalism. Even though scientists have questioned if the smog tower really works, the vertical purifying machine built on top of a sewer drain would undoubtedly find itself represented in the next electoral cycle's manifestos, an example of something concrete that has been done to intervene in a frustrating problem. Though the tower would produce a local purified bubble, it is meant to provoke affective ties to toxic nationalism.

I am interested in visualizing the workings of the multinational Taiwanese petrochemical manufacturer Formosa Plastics. The company is implicated in causing severe environmental problems: in Texas, activists recently achieved a historic settlement of $50 million to mitigate the release of small plastic pellets (“nurdles”) in the ocean; in Louisiana’s “cancer alley”, StopFormosa.org and the Louisiana Bucket Brigade fight the construction of a new $9.4bn plastic plant; in Vietnam, a chemical spill caused the country’s worst environmental disaster, threatening the livelihood of 40,000 fishermen; and in Kaohsiung, activists are pushing back against the expansion of a 20 year old naphtha cracker complex.

The literal places that Formosa inhabits – or plans to inhabit – are toxic for obvious reasons, as they have a significant toxic chemical load in water, air and soil. In Kaohsiung, the industrial infrastructure is aging and not well documented. Then, there is also China’s digital misinformation campaign leading up to the recently held Taiwanese elections, including the results that could increase pressure from Beijing. In Louisiana, activists highlight that the new facility is known to be located on two slave burial grounds. The Texas activists report that, despite their success, new plastic waste is continuously released into the ocean.

Thinking about the visual side has been more tricky so far. Building on Kim’s research on Bhopal brings to mind the ongoing attempt to map and visualize the operations of a multinational chemical industry. A group of Taiwanese journalists won the 2019 data visualization prize for an animated film about the naphtha cracker, but it’s mostly a national story. What does it mean to think of Formosa as global place?

VtP Image 1:

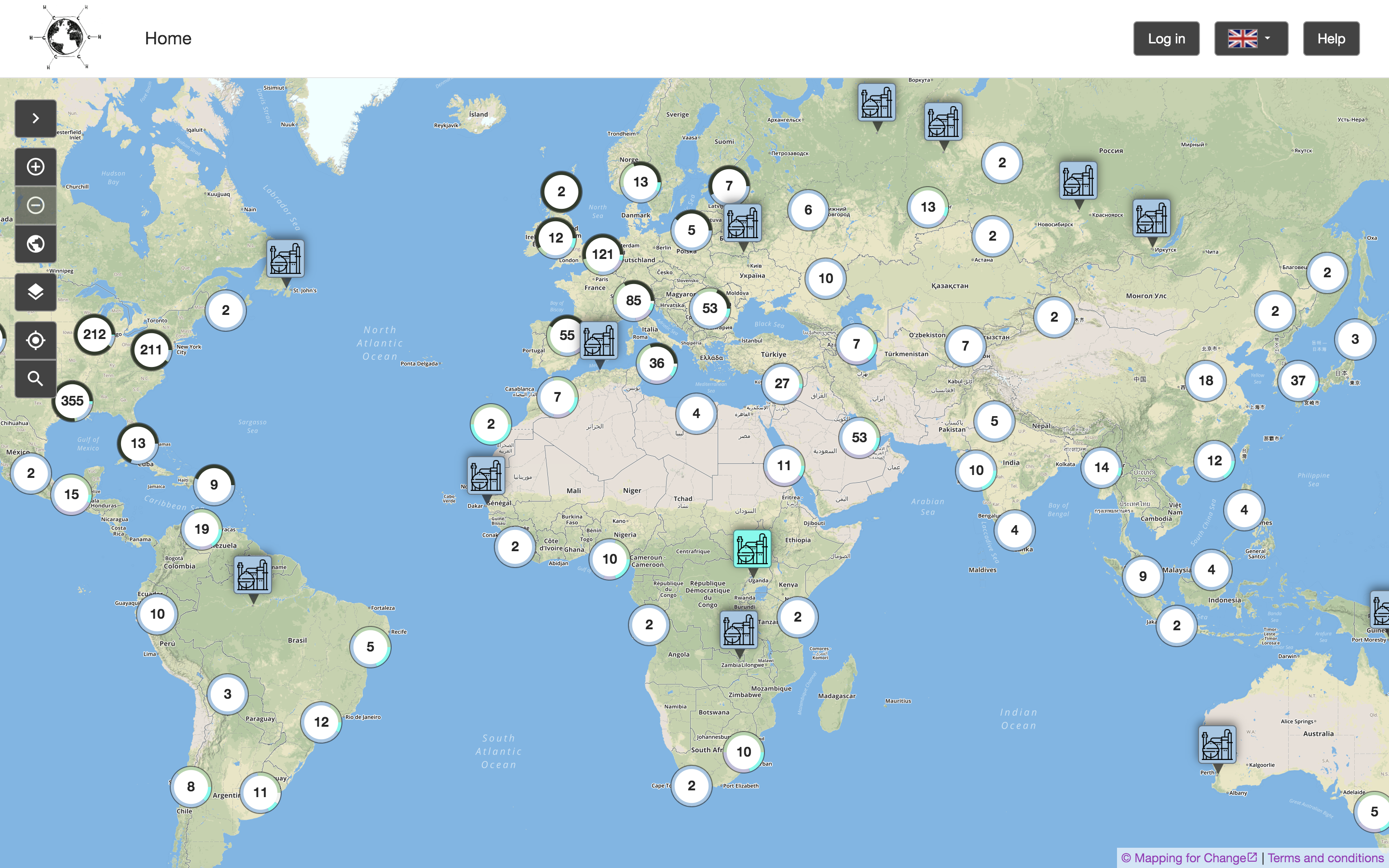

This is a screenshot I made of the "Global Petrochemical Map", an interactive visualization website. The map was created by researchers in the European Research Council-funded Toxic Expertise project. The project team's goal is to "map cases around the globe of major petrochemical sites, local communities, community and labour mobilisations, and details of emissions, environmental and safety records, photos, and media reports."

I came across the map in my search for a "global" view of Formosa Plastics, a visualization that would include all the different Formosa-run facilities. This screenshot, however, shows petrochemical plants across the globe. Certain facilities are highlighted, because they feature extra-information, including both quantitative toxic release information and qualitative data (narrations, images, ... ) submitted by users. While many Formosa facilities can be found on the map, they often feature only either of these types of data – or sometimes nothing at all. It also remains unclear what kind of data – including visuals – might be effective for this kind of website.

The visualization might serve as a reminder for the well-known STS partial view that a "god's eye" view of the world produces. At the same time, it seems to be an attractive point of entry to start mapping out all of Formosa's activities at once.

VtP Image 2:

This is a photograph of "community chemist" Wilma Subra, taken by Rick Mullin. Mullins visited Subra in her office in Southern Louisiana and conducted an interview with her. The image appeared as part of a published article on the website Chemical & Engineering News (Janurary 2020).

In the interview, Subra recounts her training as a microbiologist and chemist, who eventually became a leading consultant for the EPA, but also NGOs and other community organizations. Though she has worked on cases of industrial pollution across the U.S., she is particularly well-known in Louisiana's "cancer alley". Currently, she is involved with the pushback against the opening of new Formosa petrochemical plants.

Both the visual and article focuses on the printed "emission data and regulatory filings" that line Subra's kitchen table, which also serves as her office. The photograph creates a feeling of awe for the masses of paper, with Subra positioned at the vanishing point. The author highlights how Subra's company, starting with a small set of employees, eventually became a "one-woman shop."

I chose the image for my essay because of this effective contrast, certainly heroic contrast – the masses of paper that a single engaged scientist is challenged to wade through. It also visualizes my own research concern with "archiving for the Anthropocene" – what will ways of storing, accessing and analyzing toxic environmental data need and look like in the future?

Further, in terms of literal place, where will the data be stored? Interestingly, the article does not raise the question of where all of these files could be kept. Subra recounts instances where she and her apartment have been violently attacked by potential goons of the petrochemical industry. Keeping records in your own home raises concerns of safety and vulnerability, of data and its scientists.

VtP Image 3:

This photograph is courtesy of Mammoet, a Dutch company that brands itself as the "global market leader in engineered heavy lifting and transport." The visual was featured in a 2019 report by ProPublica about the cost-cutting strategies of petrochemical companies. In Louisiana, these companies benefit from tax breaks, while promising both permanent and temporary jobs. As the article shows, the companies forego a lot of the promises by assembling chemical plants outside of the US and then shipping them back.

The visual is a documentation of this practice, the caption reads: "A steel bridge was constructed over the Mississippi River levee so that pieces of a methanol plant could be unloaded from a ship that carried the facility from Chile."

Following anthropologist Stefan Helmreich's work on the FLoating Instrument Platform (FLIP) – a research vessel that can move from horizontal to vertical – the visual of the massive steel construction on the levee creates a sense of wonder. Something similar be said for the photograph taken of the ship delivering parts of the chemical plant.

Verticality is also what matters in Formosas work:

"One important way in which we differentiate ourselves in our marketplaces is through the extensive vertical integration of our supply chain. We produce oil and gas and transport these raw materials through our subsidiary Lavaca Pipe Line Company, then our Formosa Hydrocarbons Company processes natural gas into its components for use by our production plants. In addition, many products are delivered to our customers through our own fleet of large, modern railcars."

Though this description is of the chemical refining process, the visual might serve to push back against the smooth and effortless depiction of assembling a chemical plant in the first place.

VtP Image 4:

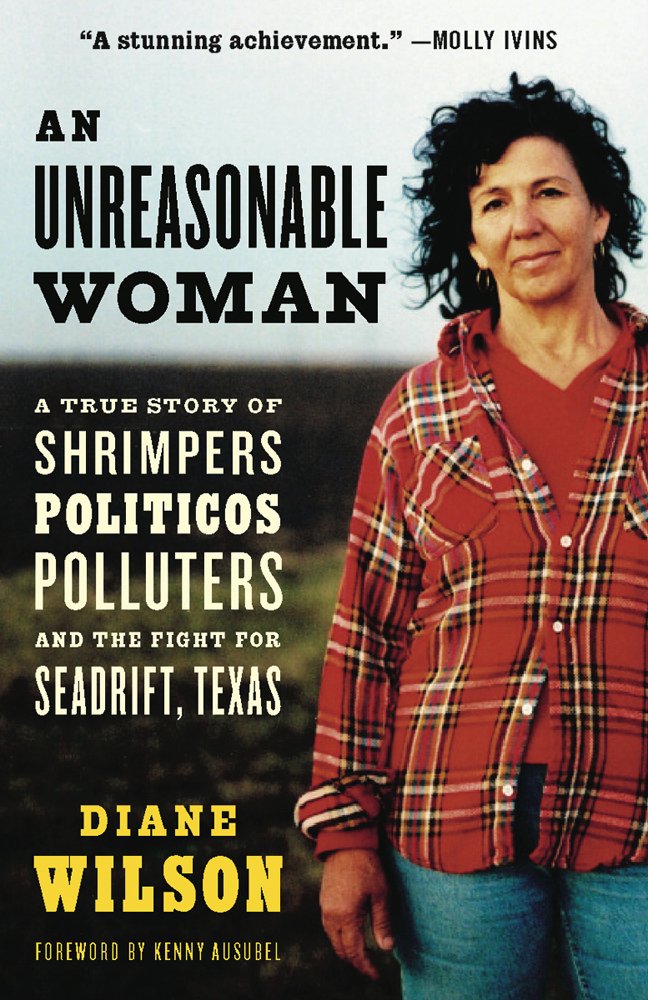

This is the cover image of the autobiography "An Unreasonable Woman", written by Diane Wilson and published in 2005. Wilson grew up around Seadrift, TX and made a living as a shrimp fisher. More than 30 years ago, she became invested in fighting petrochemical facilities in the area, including Formosa Plastics, which opened their 2,500 acre complex in 1983.

Wilson's career as an activist is remarkable in many ways. In a 2019 interview, she recounts how learning about the high air pollution in the area – first published in light of the Bhopal disaster, right-to-know legislation and toxic release inventories (TRI) – got her interested in knowing more. Early on, companies she called up would refuse to hand out numbers to her and overall did not take her seriously. Later, she would engage in various civil disobedience actions, including a hunger strike and sinking her own shrimp boat on a Formosa discharge pipe. Most recently, a group of activists that she is part of won a $50 million lawsuit against Formosa; in the interview, Wilson says that she feels like it's "the first time that justice has been achieved."

The photograph is striking for her determined outlook and posture, paired with her every day (work?) clothes. It indicates a dynamic of activism in a toxic environment (in the double sense) -- e.g. not being taken seriously, being talked down to. It also points to the different stakeholders involved in the fight againstt Formosa, such as shrimpers depending on their livelihood.

The photograph of Wilson and the re-appropriated slur of being "unreasonable" have become somewhat iconic in the protest against Formosa. In their interview, LA-based environmental activist Brooking Gatewood mentions that she was so inspired by Wilson's work that founded an environmentalist group named "Unreasonable Women."

In late March, I will be part of a small group visiting Wilson in Texas. Including her image in this photo essay, I hope to think further about what makes the image ethnographic (in addition to and beyond autobiography) and how it could be used in contrast or comparison with other visuals across the submitted projects.

VtP Image 5:

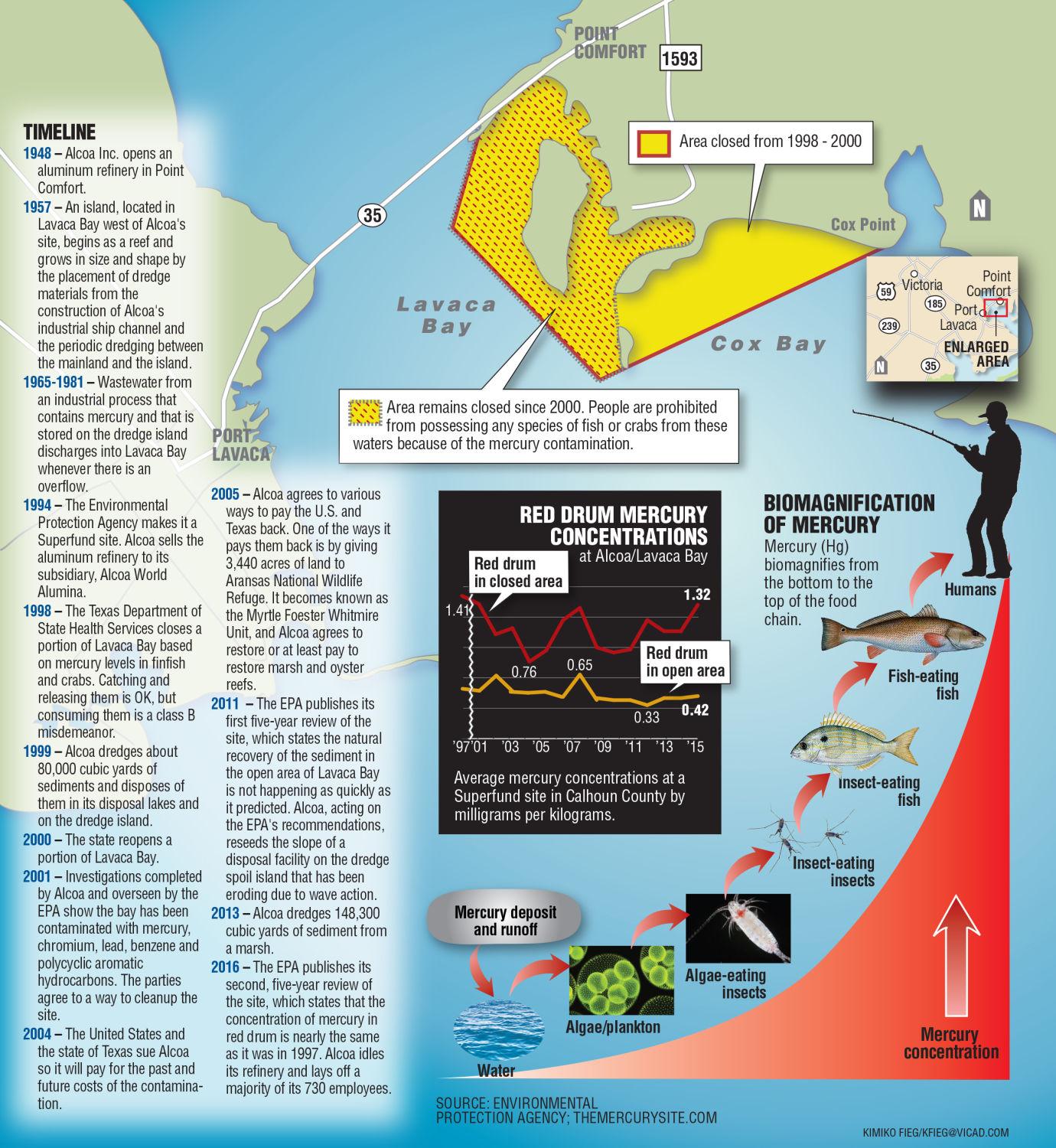

In Point Comfort, TX, the aluminum producer Alcoa has polluted the waters of Lavaca Bay with mercury, leading to an EPA superfund site. This visual provides a timeline of the pollution history, an overview of the affected area and the process of biomagnification throughout the food chain. In a 2019 interview, Diane Wilson highlights that the plastic pellets discharged by Formosa have shown to absorb the mercury, producing compounded toxicity.

I included the image here for two reasons: 1) looking at the map after listening to the interview reveals the exclusions that are inevitably produced by the map's focus on mercury 2) it serves as a token representation for maps that aim to be comprehensive and bring different data sources into view (historical development of the plant, geographic markers, scientific graphs).

How am I defining "toxic university?" How is "toxic" different than other analytics?

"Toxic" means a combination of circumstances (geography, people, time, space, culture, etc.) that fuse together to create a vulnerability to illness. I use "toxic" in the context of the university to show that its segregationist practices create an amalgamation of toxicity that is spread through narratives that normalize their practices of racist, classist, and sexist exclusions.

"Morningside Heights. New York is a city of neighborhoods, each with its own character and personality. Our neighborhood -- Morningside Heights -- is an ideal setting for a great university. Situated on hilly riverside terrain about sixty blocks north of Midtown, it affords easy access to the city's cultural resources and attractions. Friendly, lively and sophisticated, it's an eminently livable residential neighborhood. Look for Morningside Heights just north of the city's Upper West Side, between 110th Street and 125th street. Broadway -- the 'Main Street' of New York City as well as Columbia University -- takes on a collegiate air. There, on the east side of the street, the handsome George Delacorte Gate opens onto the Columbia campus.

A leisurely walk through the neighborhood takes you past a number of other important educational and cultural institutions, including Barnard College, the Union Theological Seminary, the Jewish Theological Seminary, the Manhattan School of Music, Teachers College, the Interchurch Center, Riverside Church and the Cathedral of St. John the Divine -- a lively center of community life which, even though it's still being completed, is the largest Gothic cathedral in the world. Small wonder that Morningside Heights is often called the 'Acropolis of America.'"

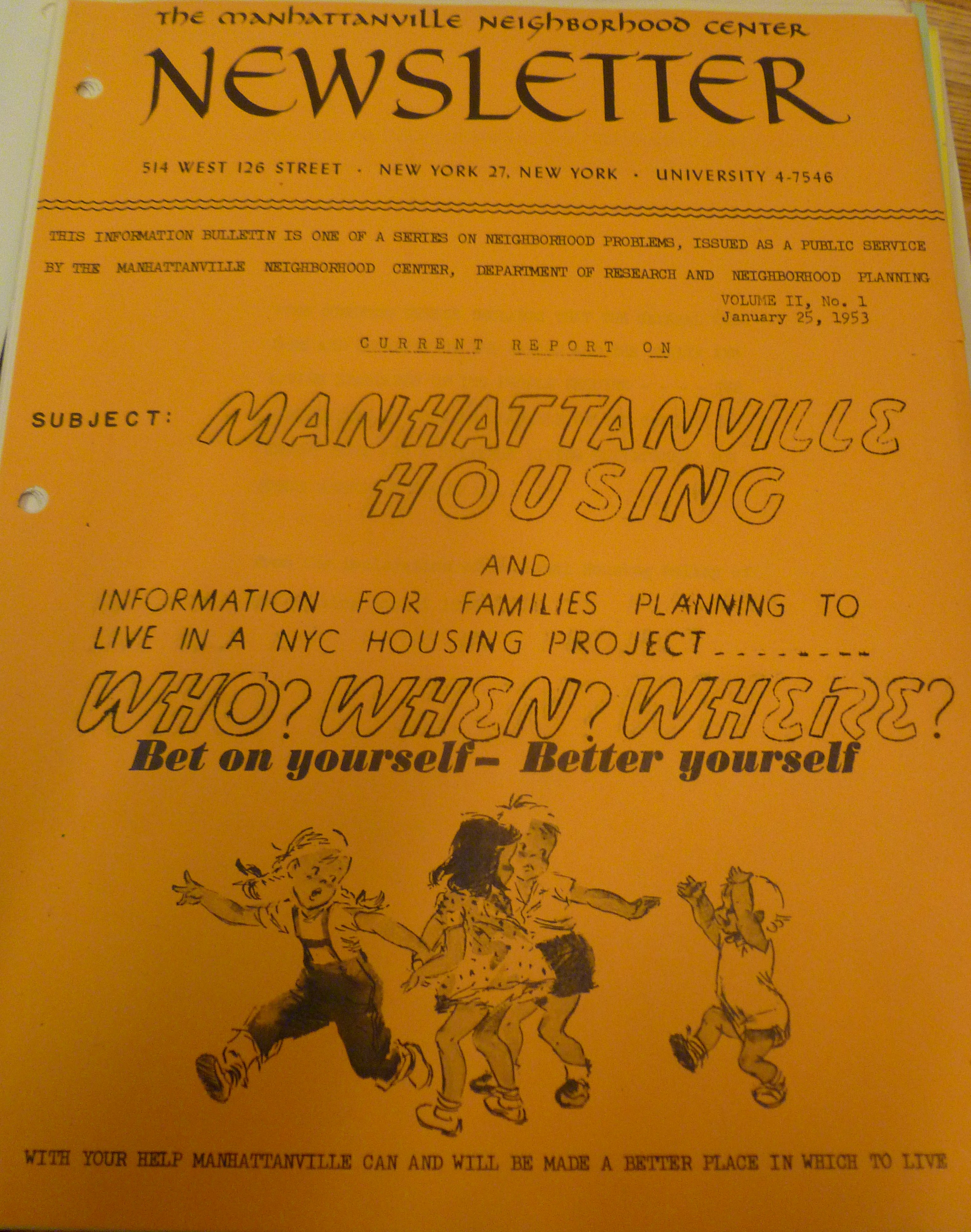

The present circumstances of gentrification in West Harlem can be traced to the very origins of the Grant and Manhattanville Houses, a case in which public housing was utilized to manage the residents in the community surrounding Columbia University. Grant and Manhattanville Houses were built to house low-income families as part of a plan developed by Morningside Heights, Inc. (MHI, renamed Morningside Area Alliance), a conglomeration of local educational, religious, and residential institutions seeking “to promote the improvement of Morningside Heights as an attractive residential, educational, and cultural area.” According to Christiane Collins, a resident and unofficial historian of Morningside Heights during the mid 1900s, MHI aspired to an ideal “American suburban-like environment, draped in an academic gown: economically and culturally homogeneous, free of ‘undesirables’ and implying discrimination along both economic and racial lines.” This particular image portrays the very population deemed acceptable by the Columbia administration: light-haired, white children, the likes of whom are conveyed as the idealized residents who will remove the present "blight." By representing these white children as the ideal citizens, Columbia and the city of New York reaffirm antiblackness. By encouraging residents of Grant and Manhattanville to "better" themselves, representing the white children as idealized, innocent, and antithesis to "blight," the implication is that to "better" oneself is to engage in antiblackness.

Photo taken by author in the Columbia University archives.

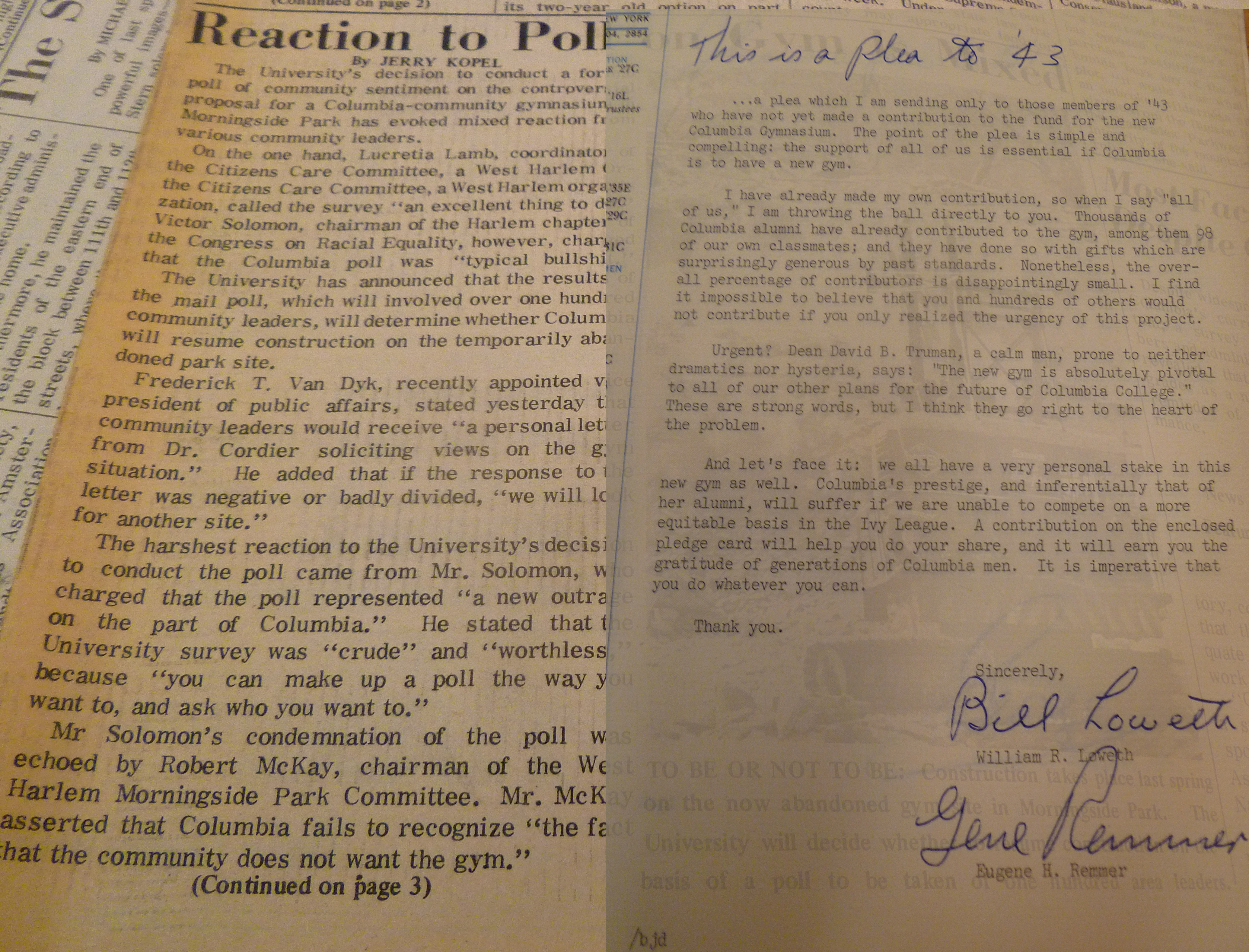

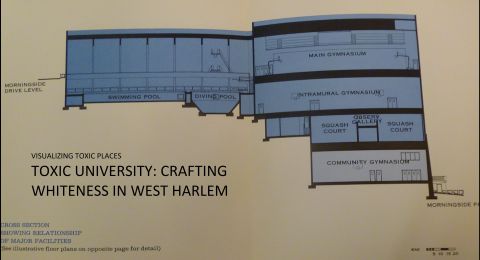

In 1968, Columbia University announced the plan to build a “quasisegregated” gymnasium in Morningside Park under an agreement with the State of New York, perpetuating the ideal of diverse but controlled spaces and the protection of institutional interests--thus propogating the same toxic narrative in support of segregation in development as a form of power. To be built on the hill of Morningside Park, the gymnasium plan consisted of Columbia’s eight-floor space resting on top of a two-story structure to be set aside for community access. While part of the same building, the Columbia University entrance was to be at the top of the park while the Harlem entrance would be on the other side of the building, thus resulting in absolute segregation between Columbia affiliates and residents from Harlem. Through the design of this gym, Columbia portrayed its commitment to a segregated university and neighborhood overall. In this particular image, the community clearly stood against the gym and noted the fallacy of taking polls asking their opinions, whereas on the other hand Columbia sought contributions from alumni urging that this gym was absolutely vital to the university's future. Such urgencies are still implemented by the university as it seeks out support for the latest Manhattanville Expansion.

As tensions increased between the institutions and the surrounding community, residents of the neighborhood organized in consortium with Columbia University students and professors, politicians, and community organizations to oppose the gymnasium plan in full force. Columbia commenced construction regardless of protests, only to face more opposition from students in the spring of 1968 when demonstrations shut down the University. Then-president of Columbia University Grayson Kirk resigned and with his resignation came the resignation of both the plan for the gymnasium as well as (temporarily) the vision for the Manhattanville Expansion, which required the use of eminent domain and thus would potentially arouse greater conflict than the gymnasium plan (Chronopoulos 2012: 51). Part of the Morningside General Neighborhood Renewal Plan, the Manhattanville Expansion was intended to be shared with noninstitutional users and residents, with a focus on creating a middle-class commercial, institutional, and recreational space. However, due to lack of funds and fear of opposition, interim President Andrew Cordier chose to cancel the Expansion. Instead, with I.M. Pei as master planner, Columbia proceeded to build above and below ground, within the main campus (Chronopoulos 2012: 51-2).

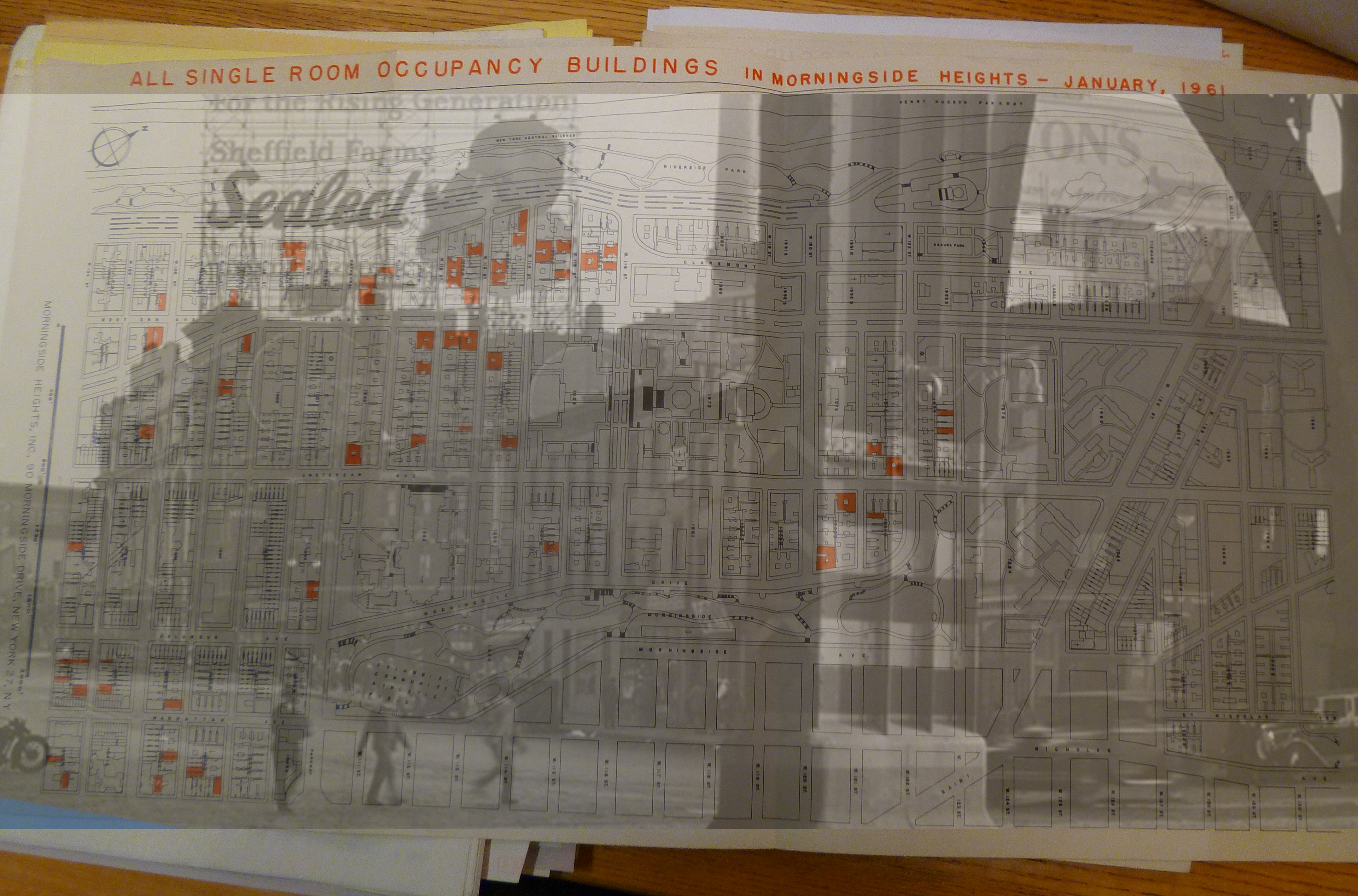

The map at the front of the image indicates the remaining SRO's (single resident occupany) that were target by Columbia University for "urban renewal," whereas the image behind conveys Manhattanville's history as represented by Columbia. This is informed by Columbia's toxic, public reminiscing of an industrialist, whitened past in Manhattanville of factories (such as the Sheffield milk factories) while ignoring the histories of “urban renewal,” displacement, and the weaponization of “blight” throughout West Harlem that displaced majority of the Black and Puerto Rican population (I find it interesting to take note of Sheffield's campaign targeting the "rising generation" of white babies).

By the 1950s, Columbia and other institutions of the neighborhood decided to remove low-income residents from the surrounding neighborhood through a campaign against SRO’s, the displacement of thousands of residents, and the rapid acquisition of buildings. Tenants were forcibly removed by various means: sealing dumbwaiters so that garbage had to be carried out in person, allowing elevators to break down, physically removing “undesirables” from buildings, plugging keyholes with wax hoping residents would be blocked out of their apartments, and at times using police officers to harass tenants and search their apartments for something illegal (Chronopolous 2012: 46). Residents resisted their forced removals, typically only delaying MHI’s plans while at other times derailing them, the great majority of people taken to court being African Americans.

The manners in which these processes have been largely raced and classed is not included in general discussion of the history of the neighborhood, and thus supposedly permits Columbia to pursue its aims. This in turn justifies privatization of land via the use of eminent domain, the likes of which propagates knowledge as a public good. This in turn elides the racist, classist, and sexist undertones of their plans by perpetuating a liberal narrative of allegedly incorporating the “community” into the academic fold while simultaneously displacing and/or disenfranchising those deemed not to fit within that fold.

SRO map photo taken by author at the Columbia University archives. Sheffield farm ad + photo of Manhattanville area taken from the Manhattanville website Columbia manages, specifically the "History" portion.

An art piece by Kiyan Williams entitled “An Accumulation of Things That Refuse to be Discarded.” Made in 2019, it is about 150 lbs (the weight of a human body) of bricks from a residential building in West Harlem that was demolished by Columbia University in order to build its Manhattanville campus (including in the gallery in which the work is displayed). The bricks are suspended from an entanglement of braids. I find this work to be materially, aesthetically, and socially stunning, invoking a sense of uneasiness, a sense of the toxicity embedded in Columbia's practices, yet a beautiful representation all the same. This work depicts a central theme of the work I seek to engage in: how is gentrification unsuccessful in its attempts to ransac, destabilize, and whiten communities in New York City and other major cities? What happens to the material and social forces that once stood in place of Manhattanville and other such developments? What does “eminent domain” mean, not just legally but socially? What role do artists in the city have in speaking truth to power in light of shifting demographics and politics? What is it about the aesthetic of this work that is both frightening and upsetting, potentially causing a physical reaction of being caught off-guard?

Masculinity and whiteness are embedded in narratives of development and perceptions of the “greater good.” Such narratives categorize residents in West Harlem, determining who may participate in the resources Columbia offers and who is excluded, who can participate in urban planning and who is ignored, who is sought out to participate in governance (whether in housing developments’ governance or city’s governance, University’s governance or federal government’s governance), who is policed and who is not. Toxicity in this case is raced and classed, embedded in historical practices of urban renewal and order maintenance that have been implemented in New York City since at least the early 20th century.

Columbia’s discourse of “reimagining” the community in Manhattanville with their Expansion, including saving the neighborhood from blight and “bringing jobs,” undercuts the fact that their Expansion displaced many businesses and people, discounted the Community Board’s designs for the neighborhood based on what the community wanted, and reenacts earlier forms of urban renewal as well as securitization. Their perception is one of coming to save the neighborhood and revitalize it, without taking into account how it negatively impacts residents, or at least does not benefit them in a way a mixed-used development might have. Residents of Grant Houses have taken the microphone into their own hands, using the Community Benefits Agreement funding, to express their view of community via a recently opened radio station and to show that they are not isolated, but are part of a broader, wide-reaching network of actors. Giving a face to their name, the residents push for recognition and representation amidst toxic narratives and a toxic landscape that tends to value and promote certain forms of knowledge over others.

In the latter part of the nineteenth-century, representations of poor people and their neighborhoods were complemented with the emergence of documentary photography. The integration of photographic images in sociological research developed a knowledge system premised on the belief that photographs could not lie and that cameras captured reality and presented subjects in a truthful manner (Chronopoulos 2014, 209). For theorists seeking universal force-causing claims to explain social phenomena, housing, and neighborhood conditions, illiteracy and poverty became omens of gender and sexual pathologies that could topple the rational order of cities and even the nation (Ferguson 2004, 77).

The politicization of aesthetics in the closing decades of the 19th century proved to be a powerful discursive tool for Progressives who sought to eliminate perceived social disorders engendered by industrial urbanization vis-à-vis the wholesale spatial reconfiguration of cities. As Ferguson states,

Postulating sexuality as a general and diffuse causality provides an example of how sexuality came to mean much more than eros, “sexual instincts”, and practices but came to signify a host of apparently “nonsexual” factors (Ferguson 2004, 77).

Published in 1950, the first comprehensive plan proposed for Washington, D.C. identified Southwest as a “problem area” suffering from urban “blight” in need of redevelopment (NCPPC). At the end of 1952, with the passage of the first urban renewal plan for a Southwest Project Area B[i], urban renewal moved from the planning stage to the action stage, triggering a wave of racial dramas in cities across the U.S. Located in the 700-block area of 4½ Street SW, Frank’s Department Store was well within the 76-acre boundary of Project Area B. Faced with the prospect of losing his business Mr. Morris and neighboring business owner Goldie Schneider refused to sell to the RLA. To prevent the government from taking their properties by eminent domain Mr. Morris and Mrs. Schneider filed suit in federal district court, challenging the constitutionality of the DCRA. They argued the government’s ability and scope to take and transfer private property to private developers as part of a project to eliminate “blight” does not constitute a legitimate “public use.” Rather, the taking of private property from one business owner for the benefit of another business owner under eminent domain amounts to an unconstitutional taking, thus violating the Public Use Clause of the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Contending their businesses were not “blighted” (Fig. 3), claimants further argued that since the DCRA had not defined the term “blight,” the RLA could not apply this ambiguous term to all of Project Area B. That said, however, the circuit court dismissed their allegations and the case was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which upheld the decision and reaffirmed the constitutionality of the DCRA. The conflict between Morris, Schneider, and the RLA highlights a critical tension in American jurisprudence during the political economy of the early Cold War: the struggle to balance an image of the U.S. as a formally liberal-capitalist nation against rationalizations for sustained maldistribution along social divides. It also illuminates an epistemic lag between the American judicial system and sociocultural developments.

[i] Southwest Washington Urban Renewal Area – bounded by Independence Avenue, Washington Avenue, South Capitol Street, Canal Street, P Street, Maine Avenue and Washington Channel, Fourteenth Street, D Street, & Twelfth Street – for more info. refer to the HABS Report by the National Parks Service.

Since its initial founding by the Residence Act of 1790, the urban geography of Washington, DC, has long become the battleground wherein the “limits of citizenship are manifest” (Carr et al. 2009: 1964). In 2006, the DC, Council enacted a Prostitution Free Zone (PFZ) code, wherein a city where prostitution has long been formally criminalized since the Mann Act of 1910, the new law constituted what may be viewed as geographies of ‘zero-tolerance’ attitude towards sex work. Under the auspices of ‘quality of life’ controls (Mitchell 2003), the PFZ ordinance (Fig. 1) vested the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) substantial discretionary powers to determine and declare a radius of blocks off-limits to already illegal prostitution or sex-work related activities for time periods lasting up to ten consecutive days (Edelman 2011: 849). Suspects ordered to disperse by the police for alleged prostitution or prostitution-related activities were “subject to a literal banishment – an evicted individual could not return to that area for the duration of the implemented zone” (Brunn 2018: 108). Refusal to disperse legitimated arrests, humiliation, and even harassment by police officers. As Alison Brunn agued: “in terms of governance and management of urban space, the figure of the sex worker was seen as a hallmark of ‘urban blight,’ whose existence in public space served as a stand-in for the existence of other stigmatized or illegal activities, such as drug use and violent crime” (2018: 107). To this end, the trans body, specifically, black trans and trans-of-color bodies were pathologized and publicized as toxifying agents in urban spaces that must be eliminated in order to mitigate geographies of ‘risk.’

In this image, cellular interstitial space is represented via the negative--the space around the blood vessel and proteins diffusing across the cellular membrane. While recently lauded as the "newfound organ" (Benias et al. 2018), the interstitium--the contiguous fluid-filled space connected by a protein lattice--remains elusive. Characterized by its inbetweenness, the interstitial is located relative to its location to other, more material structures. In its relative immateriality, the interstitial is understood only through its ability to be filled with excess fluid or pathogenic cells. For U.S. veterans exposed to burn pits--large pits used on U.S. military bases to burn war-related waste using jet fuel--interstitial lung diseases are common, though still poorly understood.

Benias, Petros C., Rebecca G. Wells, Bridget Sackey-Aboagye, Heather Klavan, Jason Reidy, Darren Buonocore, Markus Miranda et al. "Structure and distribution of an unrecognized interstitium in human tissues." Scientific reports 8, no. 1 (2018): 1-8.

It is that Third Space, though unrepresentable in itself, which constitutes the discursive conditions of enunciation that ensure that the meaning and symbols of culture have no primordial unity or fixity; that even the same signs can be appropriated, translated, rehistoricized, and read anew

Homi Bhabha (1994, 37)

"Third spacing" is a clinical term used to describe the abnormal movement of fluid from intracellular to interstitial spaces, commonly associated with burns or edema. When this fluid shift occurs, the body can experience hypovolemic shock, which is further complicated by the ways the fluid loss proves difficult to quantify as these interstitial spaces can accommodate incredible volumes of fluid. Like the Third Space in postcolonial studies, corporeal third spacing defies representation. As depicted in this image, in order to "see" the third space, the body must be altered to a state of unrecognizability; even then, in these depictions it remains unclear what the interstitial is, represented through the blankness between material structures.

Bhabha, H. The Location of Culture. New York: Routledge, 1994, p. 37.

Euliano, T. Y., J. S. Gravenstein, N. Gravenstein, and D. Gravenstein. 2011. Essential Anesthesia: From Science to Practice. Cambridge University Press, p. 34.

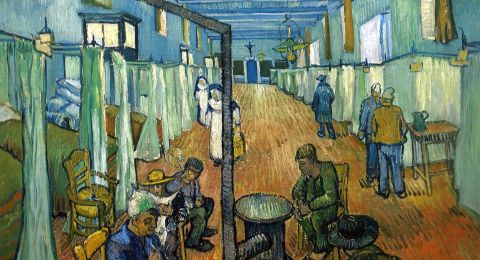

In hospitals and laboratories, interstitial spaces are spaces designed adjacent to regular-use floors to contain mechanical infrastructure. Designing these as separate spaces allows for the possibility for rearrangement of regular-use floors (e.g. turning patient rooms into operating theaters) and allows for infrastructural maintenance to be completed without interruption of patient care. But hospital interstices, I argue, are found beyond those formally demarcated by architects and hospital engineers. The interstices, as depicted in van Gogh's 1889 painting, are sites of intense engagement between patients, practitioners, and families. They are the hallways and waiting rooms and storage closets. While the "cell" of the patient room is often imagined as the center of care, the hospital corridors are often where the most important consultation and communication takes place. These are spaces of fluidity: where specialty and hierarchy bleed, where patients--waiting for their formal admittance into a cell--dwell, often unaccounted.

Interstices, in Roman Catholicism, are periods of time required by Church law between grades of Holy Orders. Under particular circumstances, a bishop may shorten the period, though it typical lasts for three months, sometimes longer.

Interstitial time can obscure recognition of toxicity. For both clergy and soldiers, interstitial time (between Holy Orders, between deployments) are built into practice as protective mechanisms in order to ensure the subject is "ready" for the next stage of their service. Yet, during interstitial periods, the body often becomes dislocated from the site of toxicity. Once toxicity is recognized, it becomes difficult to apprehend without colocation of the body.

Peering through a chain-link fence at the former location of General Motors’ Buick City, once a massive complex of factories that employed upwards of 28,000 people. All that remains now is a vast expanse of weedy concrete and the ghostly outline of the buildings that once stood here. A variety of hazardous chemicals including PFAS have been found in soil and groundwater at the site, which ranks among the largest brownfields in the United States. Visible in the background is the water tower at the Flint Water Treatment Plant, from which water from the nearby Flint River was dispensed to Flint residents from April 2014 to October 2015. Improper treatment procedures exacerbated the natural corrosivity of the water, resulting in severe damage to Flint’s infrastructure and a public health crisis. Many residents were wary of the river water from the beginning, conscious of the river’s history as a kind of toxic thoroughfare channeling the byproducts of 150 years’ worth of industrial activity along its banks. Just as that toxic history looms large within popular understandings of Flint’s water crisis, the experience of the crisis now colors popular perceptions of the Buick City site in turn. On one hand, the site has been implicated in the recovery effort, held up as a possible source of revival and opportunity, with major corporate suitors eyeing the site and promising jobs; on the other hand, it exemplifies the difficulty and expense of environmental remediation, as prospects of redevelopment have been complicated by new revelations about the extent of chemical contamination at the site as well as proposals for potentially additional extractive industries. For the most part, residents themselves have been on the outside looking in, as the land is owned and managed by the Revitalizing Auto Communities Environmental Response (RACER) Trust, created during GM’s bankruptcy to take charge of the corporation’s bad assets. Recently, RACER has begun offering tours of the site and holding informational meetings, but the extent of its commitment to engaging the community in its planning remains in question, to the frustration of neighbors and other concerned residents who feel a connection to the site.

Looking across the Flint River at a storm water outflow connected to the Buick City site. Under a dusting of snow one can discern the containment booms that have been placed at the mouth of the outflow to capture surface-level contaminants. The river has a rich and complex history for the residents of Flint. Historically, industrial activity has clustered around it, from saw mills and carriage-making shops in the 19th century to the automobile factories that earned Flint the nickname the “Vehicle City.” The consequences for the health of the river have been severe. Legend tells of the river catching on fire, of large-scale fish die-offs. Residents recall stories of illegal dumping commanded of them by their managers at General Motors. Large amounts of contaminated sediment have had to be dredged up from certain sections of the river. Over the years, the brokenness of the river—once Flint’s lifeblood—became symbolic of the brokenness of the community. Despite all of this, water quality has improved substantially since the introduction of federal environmental protections in the 1970s. Current residents kayak and fish on the river; others picnic nearby on the restored river’s edge that runs through downtown. But the river’s reputation has largely remained poor, and the picture is not all rosy. In recent years, the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality has detected PFAS in the water here—a class of chemicals also found at the nearby Buick City site. The northernmost outflow connected to that site drains into the river upstream of where the city of Flint drew its drinking water from April 2014 to October 2015. For those who use the river as a source of sustenance and recreation there are concerns that chemicals from Buick City may be finding their way into peoples’ bodies through these other routes, too.

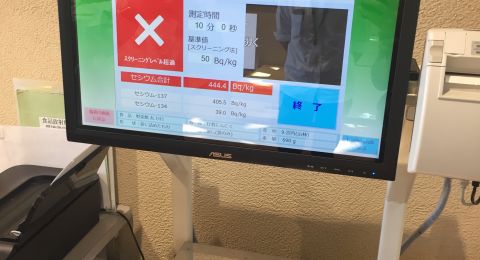

The labor of becoming a citizen scientist involves intense self-education. Activists have learned to read maps like this not out of personal interest—as a hobby citizen scientist might—but out of concern for their own survival and the survival of their children. These maps are tucked in appendices of documents only recently made available online by the EPA. Prior to that, activists had to dig through records at research libraries or make requests through the Freedom of Information Act. Even once the document is required, the barriers to understanding these documents are numerous and overwhelming: this map is in appendix B (there are 26 appendices) on page 286 of a 2,313 page jargon-riddled report that includes seven pages of acronyms as a key. This particular map is a historical map of monitoring bore-holes. Each hole has an assigned series of letters and numbers for identification and tests for a specific contaminant, also identified by a series of letters and numbers. Additionally, results are dependent upon the kind of soil or bedrock the hole is bored into, so to understand this map, one must also research the geological history of the site. Luckily, there is also an appendix and list of acronyms for those maps as well. Once the map is read and understood and the data compiled, more barriers prevent remediation. How does a concerned group of citizens—not scientists—access the politicians who have a relationship with the corporations who own and govern this site? How can they convince potentially responsible parties, that they, with no background in science, have concerns that should be taken seriously? Who would believe that a group of untrained citizens has spent months learning the esoteric language of monitoring and remediation? Who is doing whose job?

Using a combination of semiotic, ecological, and spatial frameworks, I explore how the city of Austin, Texas can be said to function as a schismotopia: a heterotopia that is simultaneously thriving and toxic in a way that denotes a complementary process of schismogenesis. In one obvious sense, Austin is heterotopian in that it has a long established, popular reputation as a “weird”, young, and progressive oasis in a sea of Texas conservatism. But behind this veil of distinction there lies another, more insidious contradiction. Austin regularly tops the charts on the best US cities in which to live, work, and to visit, coming in at #1 on the US News and World Report’s list of Best Places to Live in the USA for the past three years. However, Austin is also one of the most segregated and socially stratified cities in the US. And as a result, Austin is the only city of its size in the US whose black and brown population has been in a steady and appreciable decline for decades.

Building off of last year’s concept of Static, this photo essay continues to think semiotically about social and cultural forms of toxicity to explore how place can become schismogenetic. These series of images enable me to put forth that place, or the lived dimension of space, does not simply emerge in relation to either material space or to the hegemonic representations of that space, nor in equal relation to both; it is not simply triadic, but rather a third. That is, place is a subjective phenomenon that emerges, phenomenologically, through collective relations to the relationship between the materiality of a space and its hegemonic representation. To put this in Gregory Bateson’s terminology, place emerges at the trito-order in the way that people “learn to learn to receive signals,” or “in the changes whereby an individual comes to expect his [or her, or their] world to be structured in one way rather than an-other” (1987, 184). In their toxic form, certain changes in expectation between subjects or groups of subjects become schismogenetic in nature, meaning that they take on the quality of progressive differentiation. This photo essay explores how environmentalism, as a mode of placemaking, has exacerbated a schismogenetic relation between the Austin’s white and non-white population.

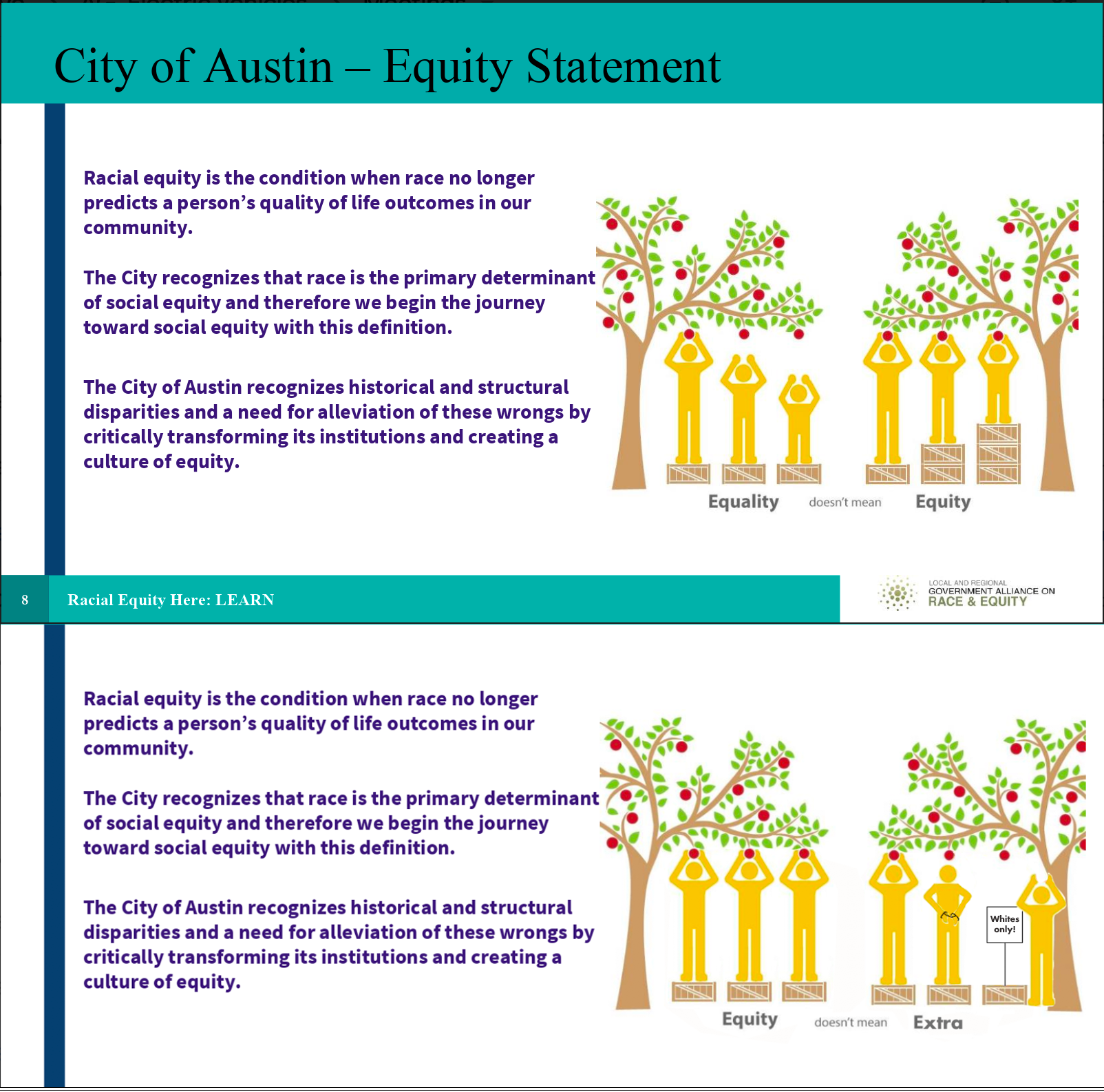

This image was produced by Tane Ward of Equilibrio Norte to provoke thought and conversation about the racism that is embedded in Austin's contemporary mode of placemaking.

Staying true to its “weird” reputation, Austin, Texas is a place full of contradiction and complications. On the one hand, the Austin community is praised as one of the most environmentally conscious cities, not only in Texas, but in the United States (World Resources Institute 2004). It’s numerous city-programs—including the Water/Wastewater Department’s Dillo Dirt, Keep Austin Beautiful, Water Conservation, Austin Recycles, Energy Conservation, Public Works, Green Builders, and the Propane Program—have won state and national recognition, contributing to Austin’s international recognition as an environmental leader (Gunn 2004). It has also remained relatively strong, economically, throughout the post-2008 depression, ranking at the top of the list of fastest growing cities in the country in 2011 (Busch 2017). On the other hand, Austin is one of the most unequal, racially-segregated cities in the US. Austin’s black communities have been repeatedly displaced over the course of the city’s development (Tretter 2016), leading to a continuous loss of population share every decade since the 1920's (Busch 2017). The city also stands out in the location of poverty. Efforts to keep the downtown “clean” and “green” have inspired strong networks of community policing of poverty and homelessness, forcing much of the homeless population into the suburbs. In East Austin, where numerous neighborhoods are currently undergoing gentrification, the poverty level of black residents is regularly 2,000 times greater than other local whites (Busch 2017).

The top image in this combination is the “go to” slide for the City of Austin when they introduce their conception of equity. I've been bringing this image up during my interviews to see how it is read by more critical audiences. One of my interlocutors, Kenneth Thompson, associated this image with the national, hegemonic discourse of the city that excludes the vernacular discourses taking place in the homes of black families. “Right, like I need help, right, and so who does that really make feel better about that, right? … when they put that thing together, they probably thought, it looks good and it probably gave them the responses they thought they was gonna get. But if they did go out and add more people and add some deliberative thought to those things, right, then perhaps someone’d say, ‘Hey man, wait a minute, you’re makin me feel like I’m in need all the time.’”

In Kenneth's words, Austin is a very “liberal” place, but not a “progressive” place. The distinction he is making here is that a “liberal” place can utilize control over the public discourse to rationalize and get away with whatever agenda they have. A “progressive” place, by contrast, considers the consequences of development and policy actions for all involved parties, including the meanings and the values communicated through those actions.

Another interlocutor, Dr. Tane Ward, made similar distinction between saying things with language as apposed to images. In an interview he commented that images are "more profound than the written word. And this is why I think that people are allowed to say whatever they want, but they are not allowed to show whatever they want." This was Tane's response to the image: "which is exactly what I’m saying. You can say it... These words are good [referring to the text in the image]. This is precisely what we’re talking about… [but] people see this and they intrinsically are like, 'hmmm, I get what’s going on. They wanna give extra shit to black people.'”

The contrast between text and image in this slide bears a symmetry to the dissonance between the City’s actions and the national discourse on Austin. Austin's progressive reputation simply does not align with the lived experiences of many of Austin’s black and brown residents. This is one way of saying that, although Austin’s white and non-white populations simultaneously inhabit the same “space,” they live in and experience the city as very different "places."

Austin’s white population relates to the relationship between the ontological and discursive space of Austin in a way that enables them to assimilate their experiences into the hegemonic discourse about the city. That is, their experience does not incite Third Order Learning, or a change in their expectations for the way their city is or should be structured (Bateson 1987). Even the self-referential critique of Austin’s history, which is included in the text embedded in the image, feeds into this hegemonic perception of Austin as a socially just and progressive place. In Tane's words, "you know, 'yea, if I talk about anti-racism, I don’t have to f***ing do anything.' When in fact... they’re really promoting the continuation and even the augmentation of racism in terms of how resources are distributed."

Being born and raised in a poor neighborhood in East Austin, Kenneth was in one of the first groups of Austin’s black residents to be relocated to the “projects” in North Austin. He understands this move as effectively depriveing him and other low-income children of access to numerous resources, including local black teachers and role models. “See there was no longer no teachers there, there was no longer no doctors there, there was no longer no one that you could go and talk to that can give you a different perspective on life. … That’s part of the economic injustice, and part of the environmental injustice that you have to deal with also. And so, to some degree, what that also caused was early death. I mean, I’m 58 years old and I bet I can name you 30 people that I grew up with, that died before 30 years old. That’s not something that everybody can do, and that’s not something that everybody should be able to do. But when you think about the disparities, that’s what disparities lead to.”

Listening to stories like Kenneth’s helps to illustrate how this sort of superficially progressive image actually participates in the erasure and exclusion of black experiences. This image does so in the following ways: 1) the visualization seems to suggest that black people need “more” assistance to create an even playing field, rather than simply taking away or offsetting the present and historical structural barriers to self-determination; 2) the metaphor of height (a “natural” difference in ability) is unfit to represent these structural disparities in the quality of life between Austin’s black and white population; and 3) it is simply inappropriate to represent disparities that result from life-course changing, structural violence with primary colored boxes, apples, and stick figures.

The second image, by contrast, suggests that the City has and continues to actively participate in preventing racial equity. And it uses visual metaphors that simply hit harder than terms like "structural violence" to get at some of the difference between Austin’s progressive discourse and it’s liberal reality. The bottom image also gets rid of “height” as a metaphor for inequality and replaces it with symbols of physical (arm restraints) and legal (“Whites Only”) barriers imposed by the City.

What becomes apparent when you talk with Austin’s local black and brown populations is that they do have a dissonant relation to the relationship between Austin’s discursive and ontological space, and this has caused a change in their expectations (i.e. Third Order learning). As with all Third-Order learning, this change in expectation has the potential to be beneficial or deleterious, tonic or toxic.

Attempting to make Austin residents feel good and maintain the city’s progressive reputation may seem quite reasonable, but the dissonance between that representation and the situation of the city's black population has detrimental effects on the psycho-social dynamics of local black families. It presents young black folk with a double bind. They are being excluded from a conversation about inclusivity. I'll quote Kenneth again, “Two things happen, we start to feel like, first of all, that our voice doesn’t exist, right? And then you start trying to figure out, to some degree, why should you get involved? Why should you get involved when it appears that those who should be the architects of fairness, right, are still imbalanced with their media and with their messages?”

Kenneth went on to argue that it takes a special skill to survive in Austin as a black person, one that reflects a certain positive form of Third Order learning. You have to become good at taking in the bullshit, digesting it, and making it into something you can use to improve the situation for yourself and your family. Which is obviously a very difficult skill to cultivate.

This diagram represents an attempt to think semiotically about "place" in Austin in terms of thirds (Kockelman 2010), of a relation to a relation (Serres 1982), and as a process of trito-order learning (Bateson 1987). Aucoin (2017) emphasizes the analytic distinction between “space” and “place” where the former is understood as a medium that can be materially, structurally, or symbolically altered to take on certain meanings for different groups. The latter, by contradistinction, is defined by how a space is lived or, to be more precise, how it “comes into being through human experience, dreaming, perception, imaginings, and sensation, and within which a sense of being in the world can develop” (Aucoin 2017, 396). This distinction creates a useful binary to think with but, as toxics often elude binary thinking (Fortun 2011), I place this dialectic relation in relation to another.

Lefebvre’s now classic triadic model of social space made use of its perceived, conceived, and lived dimensions. Using this model, space, in Aucoin’s sense, can be further broken down into a dialectic between Lefebvre’s first two dimensions: the perceived and the conceived. These dimensions were derived from the structural linguistic notions of signified and signifier. But, as a Marxist humanist committed to developing theory of political practice, Lefebvre bristled at this linguistic approach’s denial of the revolutionary potential of art and other non-linguistic forms of meaning and signification. He therefore introduced “lived space” as a third term that set the dialectic off balance and allowed for temporality and difference to be incorporated into spatial structure.

While this “third term” does indeed create room for politics, given our focus on toxicity, I am interested in how these relations can become progressive in ways that are deleterious. I will put forth that place, or the lived dimension of space, does not simply emerge in relation to either the perceived or the conceived, or in equal relation to both; it is not simply triadic, but rather a third. That is, place is a subjective phenomenon that emerges, phenomenologically, through collective relations to the relationship between the ontological and the discursive dimensions of social space.

For a closer look at a breakdown of the concepts that build up to Schismotopia, see this photo essay.

This image was produced by Tane Ward of Equilibrio Norte to provoke thought and conversation about the racism that is embedded in Austin's contemporary mode of placemaking.

The segmented nature of Austin’s social space corresponds, to a large degree, with the history of its racial geography. Environmental risks are disproportionately distributed to East Austin, the area of town which, in the 1928 Master Plan, became designated as the segregated “negro district.” Since this designation, East Austin has been consistently subjected to environmental hazards.

Originally, the East Austin community was upset that the city used tax incentives to attract businesses that would bring little to no benefit to the East Austin community in which they were located (Tretter 2016). However, this focus took a notable turn after the discovery of chemical leaks and the illegal disposal of industrial waste from Austin’s Motorola Plant in 1982 and 1984. These events made local community leaders aware of the potential risks presented by having these facilities so close to home. Small sections of Central East Austin have also recently been targeted for clean-up and redevelopment, raising the property values in the area and, once again, forcing members of the black and brown community from their homes and residences. Many of Austin's liberal, progressives still consider this gentrification to be in accordance to the natural or logical development of a city. In their view, East Austin’s Desirable Development Zones are both dilapidated and cheap, and therefore the locations most suitable and in need of redevelopment. The incisive response of many local environmental justice groups is to point out that environmental racism was the cause of the dilapidation and poverty in the first place.

Asymmetrical power relations determine which environmental problems become visible as problems and therein capable of being addressed. As Tretter points out, though the ideology of smart growth rests three equal legs (economy, environment, and society), in Austin these legs have split into two factions: an economic-environmental interpretation of urban sustainability, and an environmental-social interpretation of environmental justice (2016).