“Sunshine” is a central and unifying myth for the L.A. boosterism genre. Its contributors have included not just creatives but also capitalists and spiritualists, athletes and activists, developers and public servants. What these figures, a class predominantly consisting of white settlers, all share in common is an attachment to the land as space to protect and defend.

The fortresses guarding property in L.A. include strong foundations in the senses of both a built environment and a spotless reputation. Lies folks told about their city secured the land’s value against deleterious truths about indiscernible toxins, sometimes literally lying under the ground. But I would encourage you to think of these stories themselves as a variety of toxicity.

These nine figures helped tell stories which have translated into toxic behavior at the popular and public levels: austerity, graft, sprawl, gouging rents, predatory lending, false prophecy, positivity bias, throwaway culture, and deregulation. Jarvis 1978, Nixon 1962, Mulholland 1913, Arechiga 1959, Ahmanson 1947, McPherson 1926, Retton 1984, Gehry 1994, Reagan 1966.

The distinction Walter Benjamin identified between the politicization of art and the aestheticization of politics remains relevant to reading artistry regarding L.A.’s environment. Since early landscape artists whose paintings of pristine nature boosted a case for conserving such spaces, the arts have performed ever since as a powerful political force against so-called toxicity.

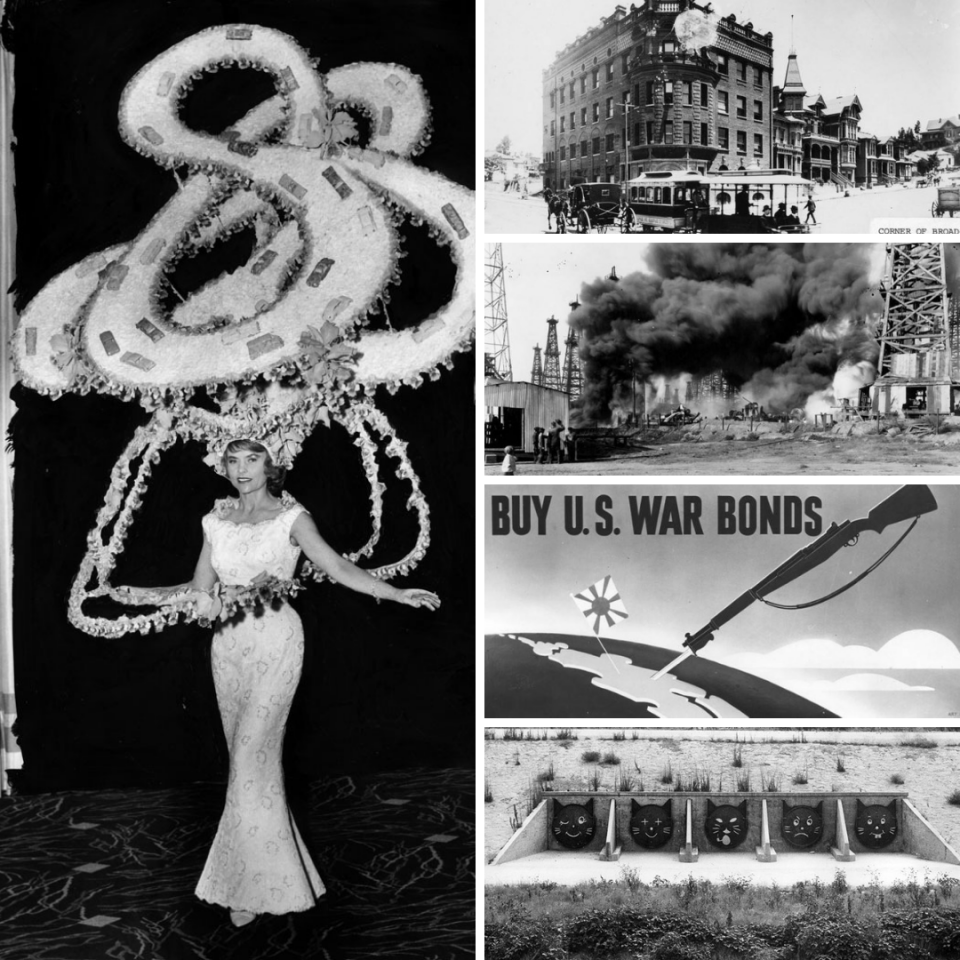

The following five images from L.A. history represent a few ways artists have nonetheless had an opposite effect on discourse about toxicity in L.A.’s environment. Beautifying places where toxicity became concentrated, at both great geographic distance and right at home, artists mobilized popular and public consent in making Southern California into a toxic waste dump.

Art-washing such moments did not universally disappear toxicity. Co-opting damage done to the environment, the arts also rebranded the freeway (1962 floral headdress), addiction (1889’s W.C.T.U. housing), a burning oil field (art photography from 1924), napalm bombing (a 1942 propaganda poster), and a channelized river (1960 storm drain cats in vernacular anticipating Pop).

Events like “race riots” carry an over-abundance of meaning as beginnings or endings of periods in U.S. urban history. Scholars will often begin their work by tracing the origins of 1965’s Watts from some mythic point of origin to a conclusive moment like a day the street violence supposedly stopped. Otherwise, scholars will highlight memory and legacies from day one.

I envision Watts 1965 as an event that transpired, not over several days, but instead as a period of toxicity which built up and wound down remarkably slowly. As your eyes move back and forth between these images, try to look for points of convergence. Which ones rhyme or align? Look also for points of discontinuity. What room do these juxtapositions leave for origins/legacy?

What more would we know about Watts if we began the story not with the Frye family (arrested 11 August) but instead with 19 April's Easter burning of the Hollywood Bowl cross or the ROTC training at the Harvard School on 20 May? How about if we ended the story not with 13 August’s arrival of the National Guard but with Gary Ballard replacing shot-out phone boxes on 22 August or Black assemblage artist Noah Purifoy’s “Sir Watts” (9 April 1966).