I am interested in visualizing the workings of the multinational Taiwanese petrochemical manufacturer Formosa Plastics. The company is implicated in causing severe environmental problems: in Texas, activists recently achieved a historic settlement of $50 million to mitigate the release of small plastic pellets (“nurdles”) in the ocean; in Louisiana’s “cancer alley”, StopFormosa.org and the Louisiana Bucket Brigade fight the construction of a new $9.4bn plastic plant; in Vietnam, a chemical spill caused the country’s worst environmental disaster, threatening the livelihood of 40,000 fishermen; and in Kaohsiung, activists are pushing back against the expansion of a 20 year old naphtha cracker complex.

The literal places that Formosa inhabits – or plans to inhabit – are toxic for obvious reasons, as they have a significant toxic chemical load in water, air and soil. In Kaohsiung, the industrial infrastructure is aging and not well documented. Then, there is also China’s digital misinformation campaign leading up to the recently held Taiwanese elections, including the results that could increase pressure from Beijing. In Louisiana, activists highlight that the new facility is known to be located on two slave burial grounds. The Texas activists report that, despite their success, new plastic waste is continuously released into the ocean.

Thinking about the visual side has been more tricky so far. Building on Kim’s research on Bhopal brings to mind the ongoing attempt to map and visualize the operations of a multinational chemical industry. A group of Taiwanese journalists won the 2019 data visualization prize for an animated film about the naphtha cracker, but it’s mostly a national story. What does it mean to think of Formosa as global place?

VtP Image 1:

This is a screenshot I made of the "Global Petrochemical Map", an interactive visualization website. The map was created by researchers in the European Research Council-funded Toxic Expertise project. The project team's goal is to "map cases around the globe of major petrochemical sites, local communities, community and labour mobilisations, and details of emissions, environmental and safety records, photos, and media reports."

I came across the map in my search for a "global" view of Formosa Plastics, a visualization that would include all the different Formosa-run facilities. This screenshot, however, shows petrochemical plants across the globe. Certain facilities are highlighted, because they feature extra-information, including both quantitative toxic release information and qualitative data (narrations, images, ... ) submitted by users. While many Formosa facilities can be found on the map, they often feature only either of these types of data – or sometimes nothing at all. It also remains unclear what kind of data – including visuals – might be effective for this kind of website.

The visualization might serve as a reminder for the well-known STS partial view that a "god's eye" view of the world produces. At the same time, it seems to be an attractive point of entry to start mapping out all of Formosa's activities at once.

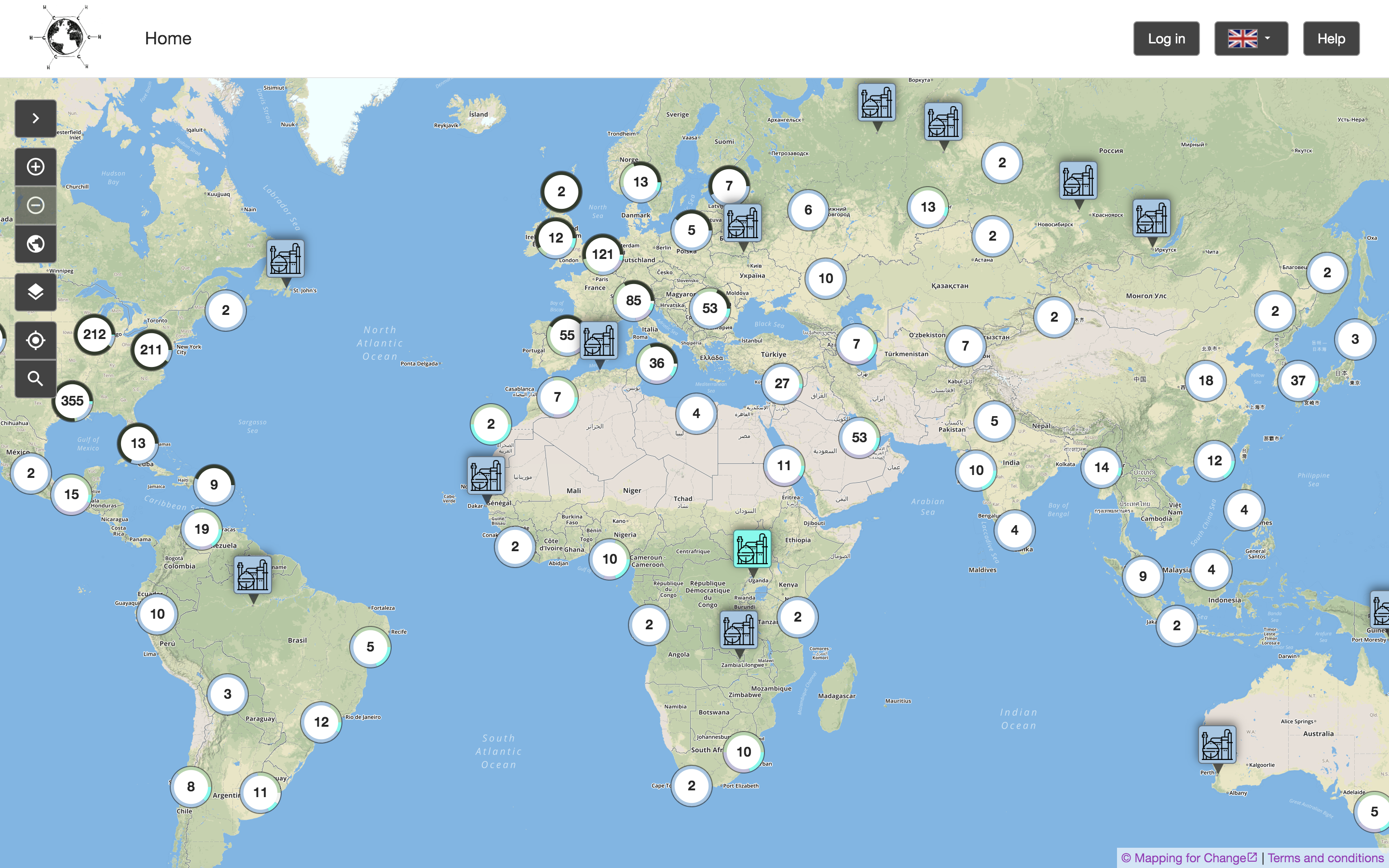

VtP Image 2:

This is a photograph of "community chemist" Wilma Subra, taken by Rick Mullin. Mullins visited Subra in her office in Southern Louisiana and conducted an interview with her. The image appeared as part of a published article on the website Chemical & Engineering News (Janurary 2020).

In the interview, Subra recounts her training as a microbiologist and chemist, who eventually became a leading consultant for the EPA, but also NGOs and other community organizations. Though she has worked on cases of industrial pollution across the U.S., she is particularly well-known in Louisiana's "cancer alley". Currently, she is involved with the pushback against the opening of new Formosa petrochemical plants.

Both the visual and article focuses on the printed "emission data and regulatory filings" that line Subra's kitchen table, which also serves as her office. The photograph creates a feeling of awe for the masses of paper, with Subra positioned at the vanishing point. The author highlights how Subra's company, starting with a small set of employees, eventually became a "one-woman shop."

I chose the image for my essay because of this effective contrast, certainly heroic contrast – the masses of paper that a single engaged scientist is challenged to wade through. It also visualizes my own research concern with "archiving for the Anthropocene" – what will ways of storing, accessing and analyzing toxic environmental data need and look like in the future?

Further, in terms of literal place, where will the data be stored? Interestingly, the article does not raise the question of where all of these files could be kept. Subra recounts instances where she and her apartment have been violently attacked by potential goons of the petrochemical industry. Keeping records in your own home raises concerns of safety and vulnerability, of data and its scientists.

VtP Image 3:

This photograph is courtesy of Mammoet, a Dutch company that brands itself as the "global market leader in engineered heavy lifting and transport." The visual was featured in a 2019 report by ProPublica about the cost-cutting strategies of petrochemical companies. In Louisiana, these companies benefit from tax breaks, while promising both permanent and temporary jobs. As the article shows, the companies forego a lot of the promises by assembling chemical plants outside of the US and then shipping them back.

The visual is a documentation of this practice, the caption reads: "A steel bridge was constructed over the Mississippi River levee so that pieces of a methanol plant could be unloaded from a ship that carried the facility from Chile."

Following anthropologist Stefan Helmreich's work on the FLoating Instrument Platform (FLIP) – a research vessel that can move from horizontal to vertical – the visual of the massive steel construction on the levee creates a sense of wonder. Something similar be said for the photograph taken of the ship delivering parts of the chemical plant.

Verticality is also what matters in Formosas work:

"One important way in which we differentiate ourselves in our marketplaces is through the extensive vertical integration of our supply chain. We produce oil and gas and transport these raw materials through our subsidiary Lavaca Pipe Line Company, then our Formosa Hydrocarbons Company processes natural gas into its components for use by our production plants. In addition, many products are delivered to our customers through our own fleet of large, modern railcars."

Though this description is of the chemical refining process, the visual might serve to push back against the smooth and effortless depiction of assembling a chemical plant in the first place.

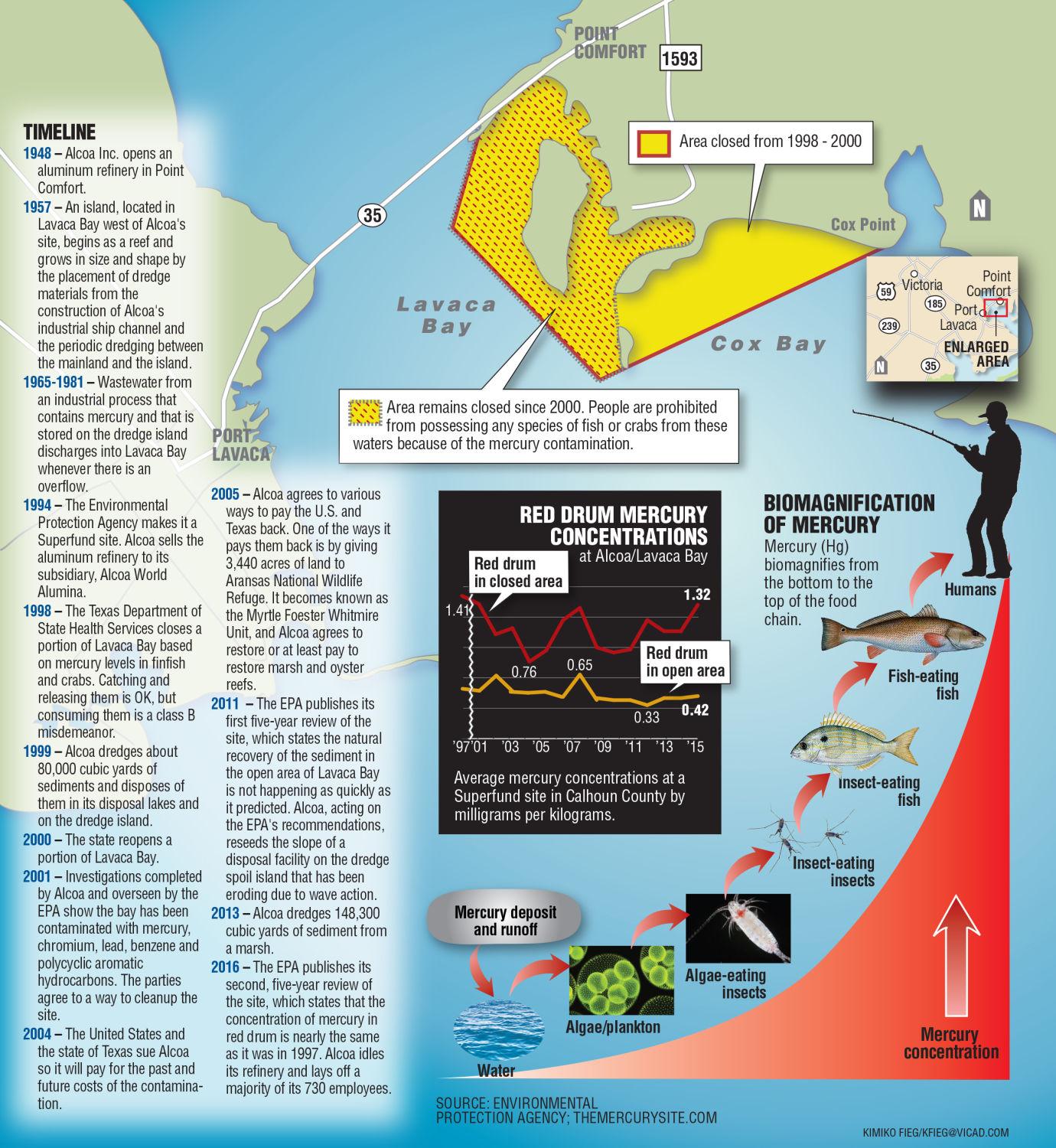

VtP Image 4:

This is the cover image of the autobiography "An Unreasonable Woman", written by Diane Wilson and published in 2005. Wilson grew up around Seadrift, TX and made a living as a shrimp fisher. More than 30 years ago, she became invested in fighting petrochemical facilities in the area, including Formosa Plastics, which opened their 2,500 acre complex in 1983.

Wilson's career as an activist is remarkable in many ways. In a 2019 interview, she recounts how learning about the high air pollution in the area – first published in light of the Bhopal disaster, right-to-know legislation and toxic release inventories (TRI) – got her interested in knowing more. Early on, companies she called up would refuse to hand out numbers to her and overall did not take her seriously. Later, she would engage in various civil disobedience actions, including a hunger strike and sinking her own shrimp boat on a Formosa discharge pipe. Most recently, a group of activists that she is part of won a $50 million lawsuit against Formosa; in the interview, Wilson says that she feels like it's "the first time that justice has been achieved."

The photograph is striking for her determined outlook and posture, paired with her every day (work?) clothes. It indicates a dynamic of activism in a toxic environment (in the double sense) -- e.g. not being taken seriously, being talked down to. It also points to the different stakeholders involved in the fight againstt Formosa, such as shrimpers depending on their livelihood.

The photograph of Wilson and the re-appropriated slur of being "unreasonable" have become somewhat iconic in the protest against Formosa. In their interview, LA-based environmental activist Brooking Gatewood mentions that she was so inspired by Wilson's work that founded an environmentalist group named "Unreasonable Women."

In late March, I will be part of a small group visiting Wilson in Texas. Including her image in this photo essay, I hope to think further about what makes the image ethnographic (in addition to and beyond autobiography) and how it could be used in contrast or comparison with other visuals across the submitted projects.

VtP Image 5:

In Point Comfort, TX, the aluminum producer Alcoa has polluted the waters of Lavaca Bay with mercury, leading to an EPA superfund site. This visual provides a timeline of the pollution history, an overview of the affected area and the process of biomagnification throughout the food chain. In a 2019 interview, Diane Wilson highlights that the plastic pellets discharged by Formosa have shown to absorb the mercury, producing compounded toxicity.

I included the image here for two reasons: 1) looking at the map after listening to the interview reveals the exclusions that are inevitably produced by the map's focus on mercury 2) it serves as a token representation for maps that aim to be comprehensive and bring different data sources into view (historical development of the plant, geographic markers, scientific graphs).

A quick overview of some archiving and exhibition projects related to Formosa Plastics:

No More Nurdles is a WordPress