Columbia University has worked in tandem with New York City to engage in “urban renewal,” aka gentrification, mapping themselves further onto the spaces of West Harlem through processes of capital accumulation and slow violence. Their engagements with such notions as “the greater good” feed into their identity as an “Acropolis” on the hill, perpetuating a form of white nationalism under the guise of “development.”

How do urban institutions such as Columbia University operate as power brokers so as to colonize their neighborhoods and craft whiteness internally and abroad?

How am I defining "toxic university?" How is "toxic" different than other analytics?

"Toxic" means a combination of circumstances (geography, people, time, space, culture, etc.) that fuse together to create a vulnerability to illness. I use "toxic" in the context of the university to show that its segregationist practices create an amalgamation of toxicity that is spread through narratives that normalize their practices of racist, classist, and sexist exclusions.

"Morningside Heights. New York is a city of neighborhoods, each with its own character and personality. Our neighborhood -- Morningside Heights -- is an ideal setting for a great university. Situated on hilly riverside terrain about sixty blocks north of Midtown, it affords easy access to the city's cultural resources and attractions. Friendly, lively and sophisticated, it's an eminently livable residential neighborhood. Look for Morningside Heights just north of the city's Upper West Side, between 110th Street and 125th street. Broadway -- the 'Main Street' of New York City as well as Columbia University -- takes on a collegiate air. There, on the east side of the street, the handsome George Delacorte Gate opens onto the Columbia campus.

A leisurely walk through the neighborhood takes you past a number of other important educational and cultural institutions, including Barnard College, the Union Theological Seminary, the Jewish Theological Seminary, the Manhattan School of Music, Teachers College, the Interchurch Center, Riverside Church and the Cathedral of St. John the Divine -- a lively center of community life which, even though it's still being completed, is the largest Gothic cathedral in the world. Small wonder that Morningside Heights is often called the 'Acropolis of America.'"

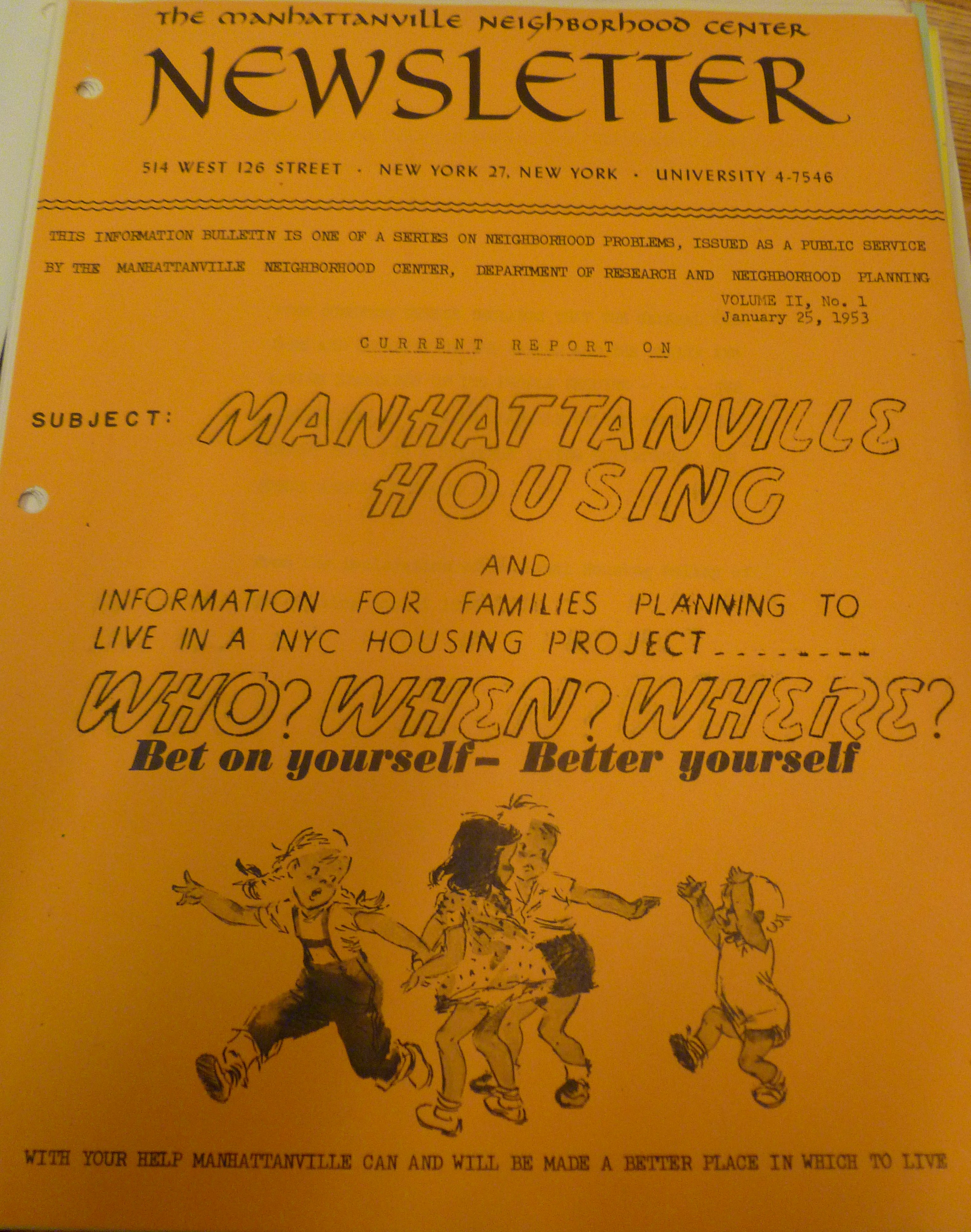

The present circumstances of gentrification in West Harlem can be traced to the very origins of the Grant and Manhattanville Houses, a case in which public housing was utilized to manage the residents in the community surrounding Columbia University. Grant and Manhattanville Houses were built to house low-income families as part of a plan developed by Morningside Heights, Inc. (MHI, renamed Morningside Area Alliance), a conglomeration of local educational, religious, and residential institutions seeking “to promote the improvement of Morningside Heights as an attractive residential, educational, and cultural area.” According to Christiane Collins, a resident and unofficial historian of Morningside Heights during the mid 1900s, MHI aspired to an ideal “American suburban-like environment, draped in an academic gown: economically and culturally homogeneous, free of ‘undesirables’ and implying discrimination along both economic and racial lines.” This particular image portrays the very population deemed acceptable by the Columbia administration: light-haired, white children, the likes of whom are conveyed as the idealized residents who will remove the present "blight." By representing these white children as the ideal citizens, Columbia and the city of New York reaffirm antiblackness. By encouraging residents of Grant and Manhattanville to "better" themselves, representing the white children as idealized, innocent, and antithesis to "blight," the implication is that to "better" oneself is to engage in antiblackness.

Photo taken by author in the Columbia University archives.

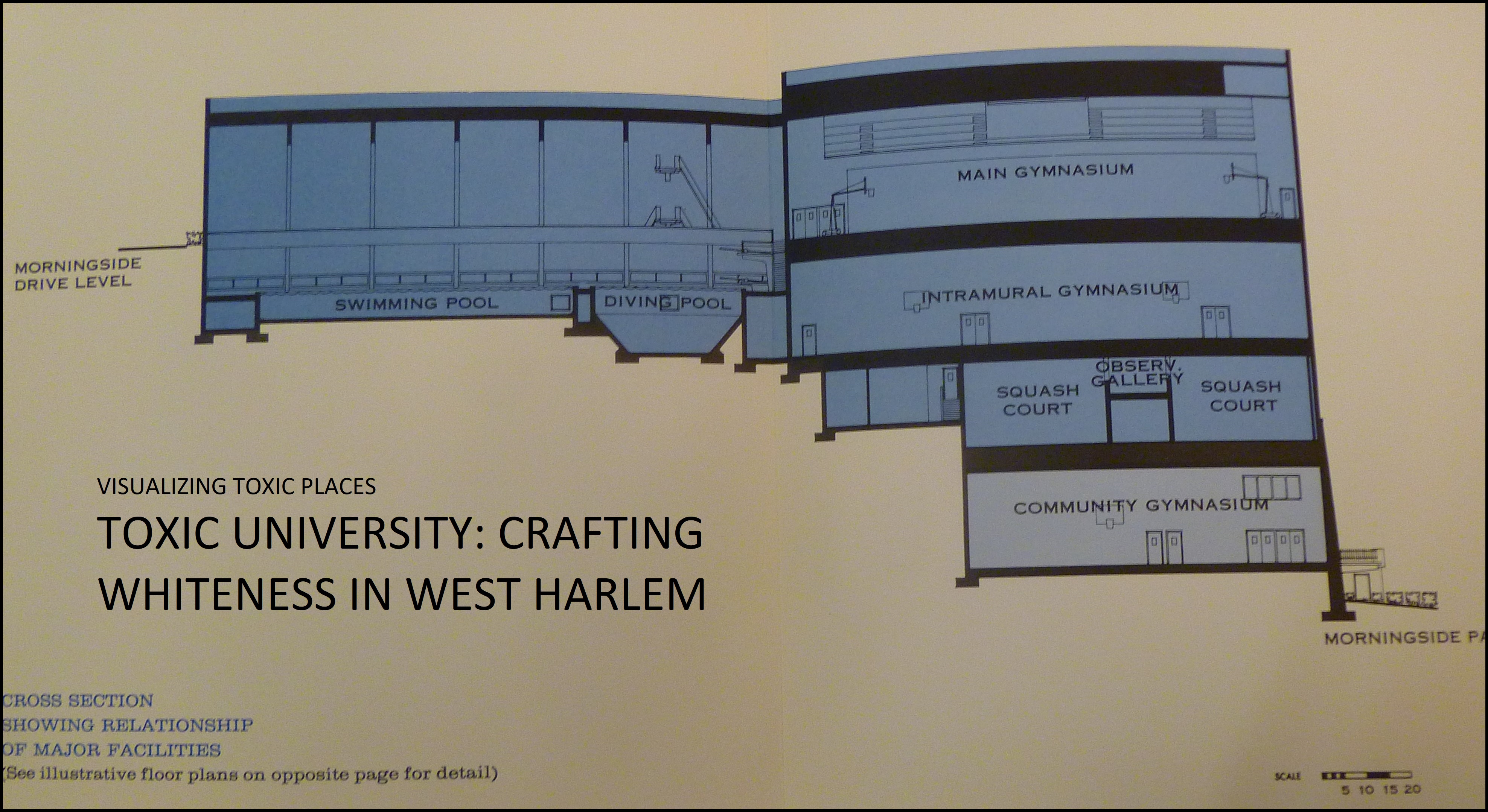

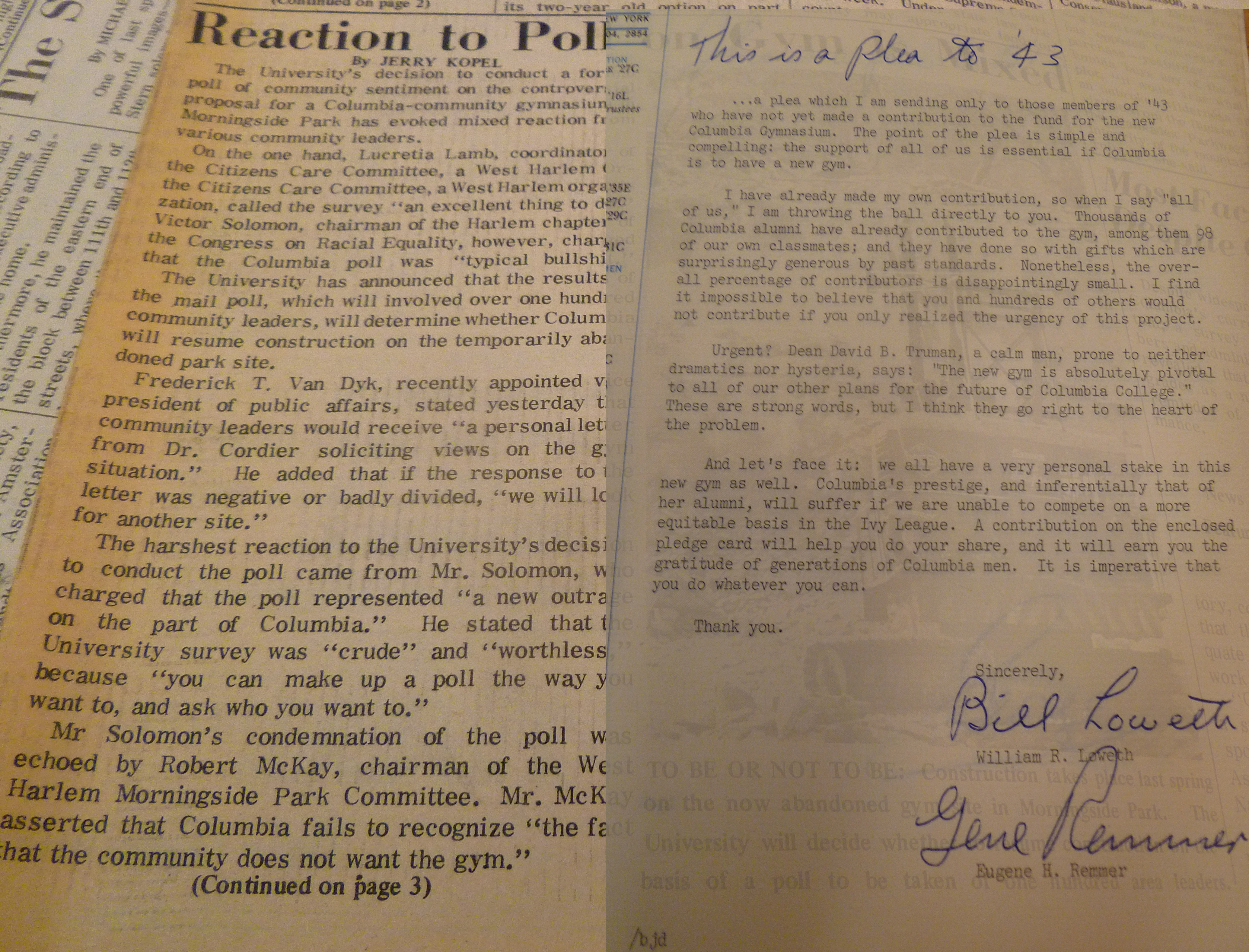

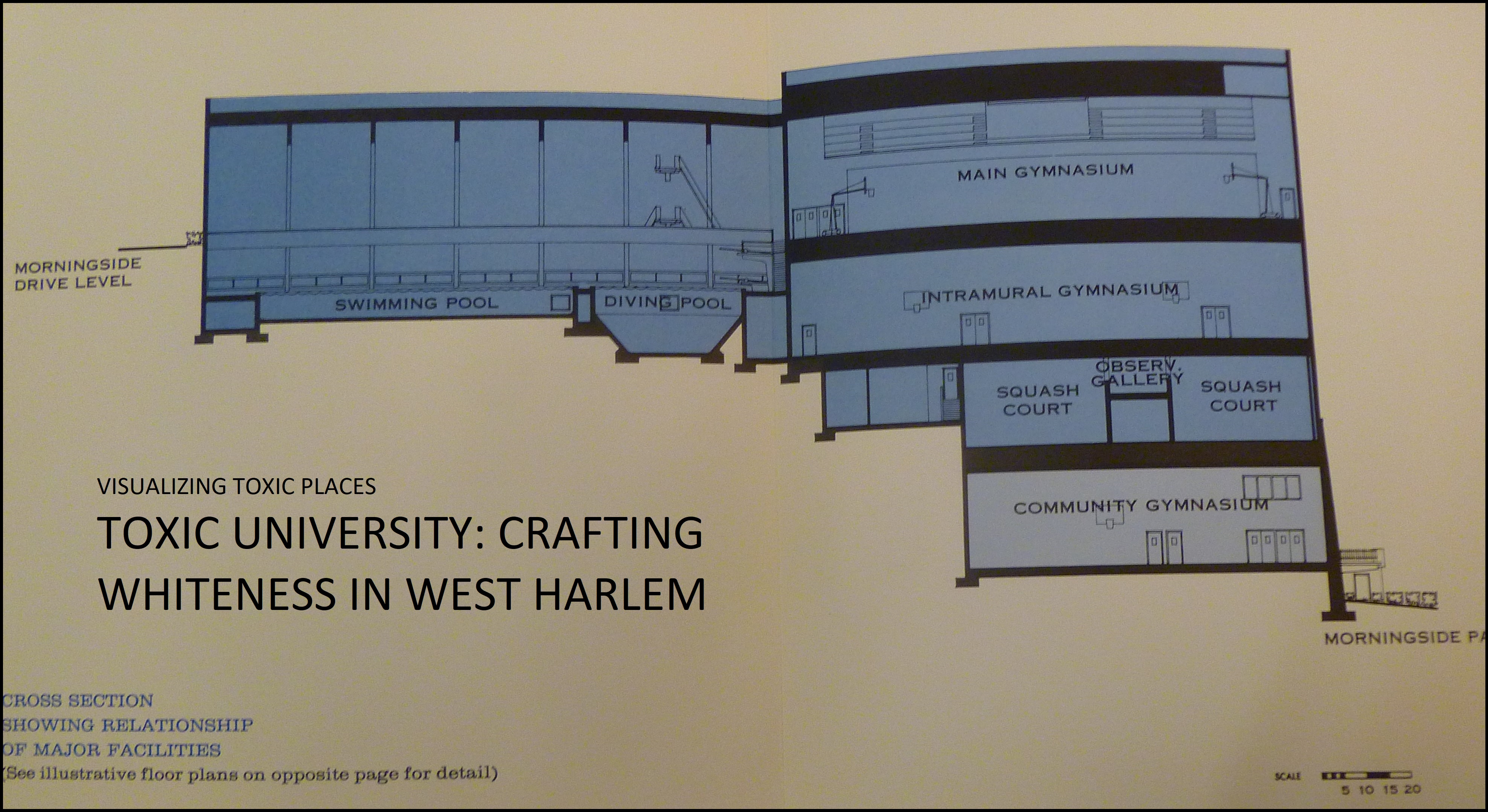

In 1968, Columbia University announced the plan to build a “quasisegregated” gymnasium in Morningside Park under an agreement with the State of New York, perpetuating the ideal of diverse but controlled spaces and the protection of institutional interests--thus propogating the same toxic narrative in support of segregation in development as a form of power. To be built on the hill of Morningside Park, the gymnasium plan consisted of Columbia’s eight-floor space resting on top of a two-story structure to be set aside for community access. While part of the same building, the Columbia University entrance was to be at the top of the park while the Harlem entrance would be on the other side of the building, thus resulting in absolute segregation between Columbia affiliates and residents from Harlem. Through the design of this gym, Columbia portrayed its commitment to a segregated university and neighborhood overall. In this particular image, the community clearly stood against the gym and noted the fallacy of taking polls asking their opinions, whereas on the other hand Columbia sought contributions from alumni urging that this gym was absolutely vital to the university's future. Such urgencies are still implemented by the university as it seeks out support for the latest Manhattanville Expansion.

As tensions increased between the institutions and the surrounding community, residents of the neighborhood organized in consortium with Columbia University students and professors, politicians, and community organizations to oppose the gymnasium plan in full force. Columbia commenced construction regardless of protests, only to face more opposition from students in the spring of 1968 when demonstrations shut down the University. Then-president of Columbia University Grayson Kirk resigned and with his resignation came the resignation of both the plan for the gymnasium as well as (temporarily) the vision for the Manhattanville Expansion, which required the use of eminent domain and thus would potentially arouse greater conflict than the gymnasium plan (Chronopoulos 2012: 51). Part of the Morningside General Neighborhood Renewal Plan, the Manhattanville Expansion was intended to be shared with noninstitutional users and residents, with a focus on creating a middle-class commercial, institutional, and recreational space. However, due to lack of funds and fear of opposition, interim President Andrew Cordier chose to cancel the Expansion. Instead, with I.M. Pei as master planner, Columbia proceeded to build above and below ground, within the main campus (Chronopoulos 2012: 51-2).

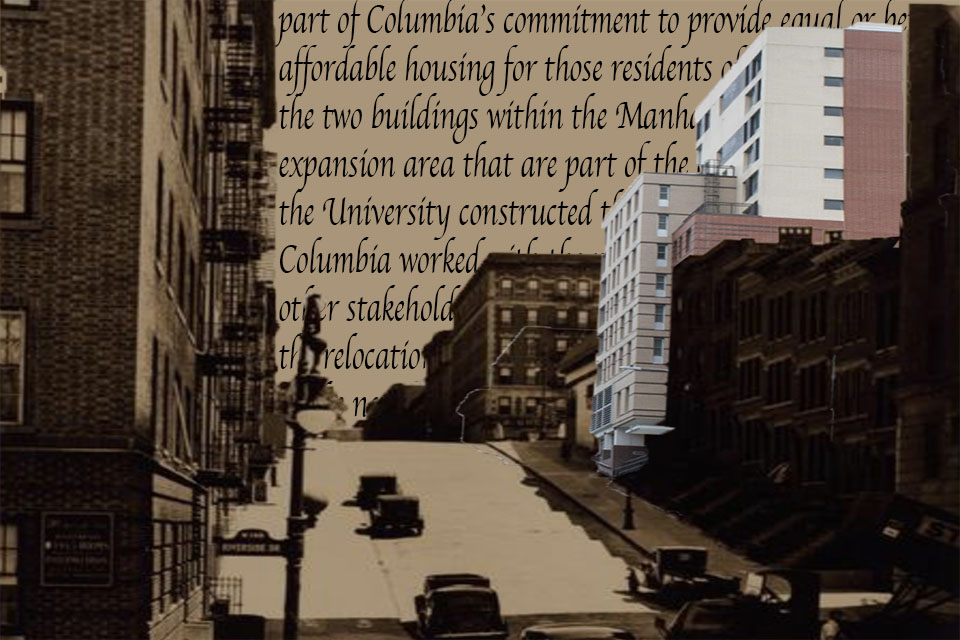

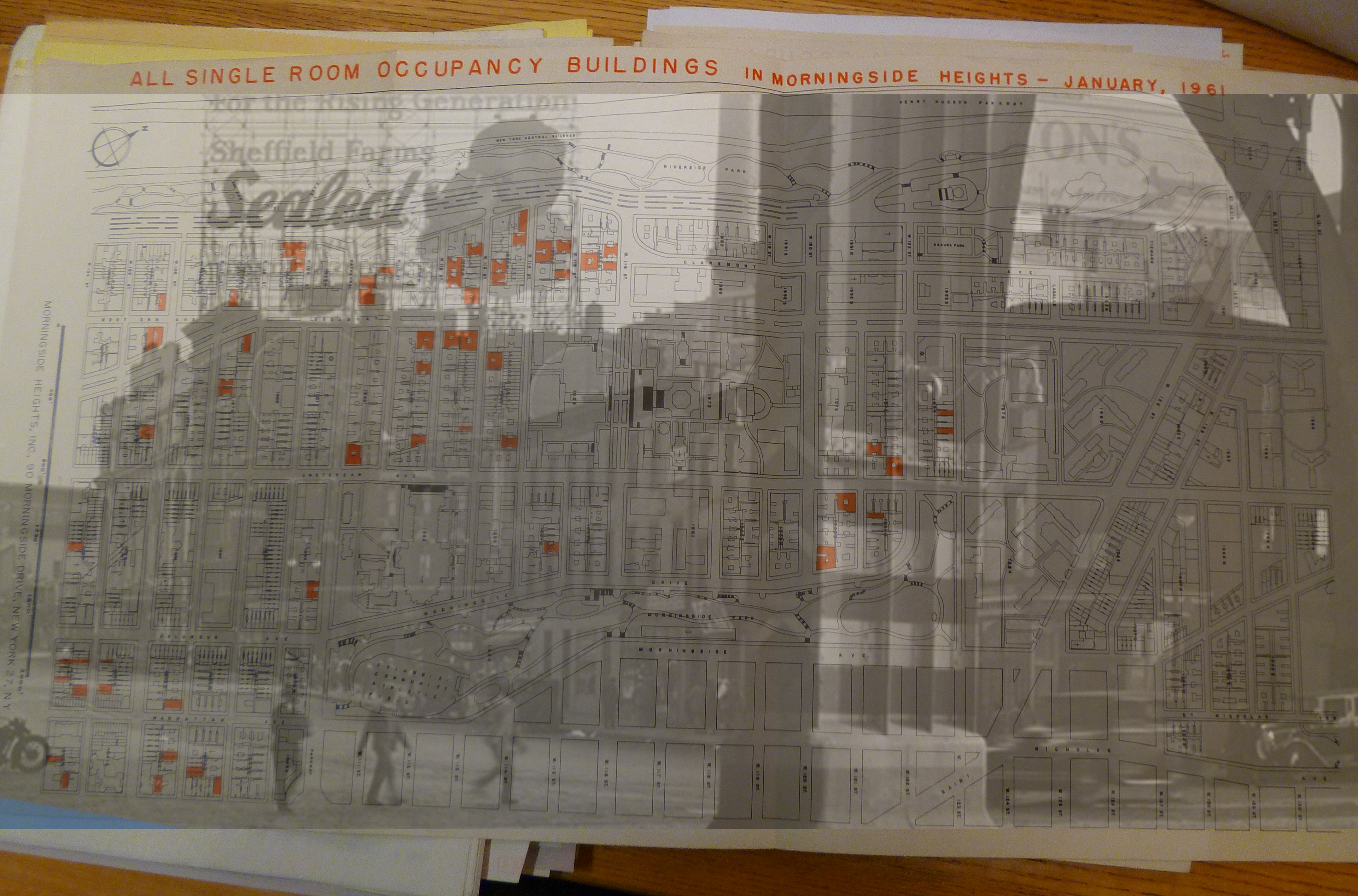

The map at the front of the image indicates the remaining SRO's (single resident occupany) that were target by Columbia University for "urban renewal," whereas the image behind conveys Manhattanville's history as represented by Columbia. This is informed by Columbia's toxic, public reminiscing of an industrialist, whitened past in Manhattanville of factories (such as the Sheffield milk factories) while ignoring the histories of “urban renewal,” displacement, and the weaponization of “blight” throughout West Harlem that displaced majority of the Black and Puerto Rican population (I find it interesting to take note of Sheffield's campaign targeting the "rising generation" of white babies).

By the 1950s, Columbia and other institutions of the neighborhood decided to remove low-income residents from the surrounding neighborhood through a campaign against SRO’s, the displacement of thousands of residents, and the rapid acquisition of buildings. Tenants were forcibly removed by various means: sealing dumbwaiters so that garbage had to be carried out in person, allowing elevators to break down, physically removing “undesirables” from buildings, plugging keyholes with wax hoping residents would be blocked out of their apartments, and at times using police officers to harass tenants and search their apartments for something illegal (Chronopolous 2012: 46). Residents resisted their forced removals, typically only delaying MHI’s plans while at other times derailing them, the great majority of people taken to court being African Americans.

The manners in which these processes have been largely raced and classed is not included in general discussion of the history of the neighborhood, and thus supposedly permits Columbia to pursue its aims. This in turn justifies privatization of land via the use of eminent domain, the likes of which propagates knowledge as a public good. This in turn elides the racist, classist, and sexist undertones of their plans by perpetuating a liberal narrative of allegedly incorporating the “community” into the academic fold while simultaneously displacing and/or disenfranchising those deemed not to fit within that fold.

SRO map photo taken by author at the Columbia University archives. Sheffield farm ad + photo of Manhattanville area taken from the Manhattanville website Columbia manages, specifically the "History" portion.

An art piece by Kiyan Williams entitled “An Accumulation of Things That Refuse to be Discarded.” Made in 2019, it is about 150 lbs (the weight of a human body) of bricks from a residential building in West Harlem that was demolished by Columbia University in order to build its Manhattanville campus (including in the gallery in which the work is displayed). The bricks are suspended from an entanglement of braids. I find this work to be materially, aesthetically, and socially stunning, invoking a sense of uneasiness, a sense of the toxicity embedded in Columbia's practices, yet a beautiful representation all the same. This work depicts a central theme of the work I seek to engage in: how is gentrification unsuccessful in its attempts to ransac, destabilize, and whiten communities in New York City and other major cities? What happens to the material and social forces that once stood in place of Manhattanville and other such developments? What does “eminent domain” mean, not just legally but socially? What role do artists in the city have in speaking truth to power in light of shifting demographics and politics? What is it about the aesthetic of this work that is both frightening and upsetting, potentially causing a physical reaction of being caught off-guard?

Masculinity and whiteness are embedded in narratives of development and perceptions of the “greater good.” Such narratives categorize residents in West Harlem, determining who may participate in the resources Columbia offers and who is excluded, who can participate in urban planning and who is ignored, who is sought out to participate in governance (whether in housing developments’ governance or city’s governance, University’s governance or federal government’s governance), who is policed and who is not. Toxicity in this case is raced and classed, embedded in historical practices of urban renewal and order maintenance that have been implemented in New York City since at least the early 20th century.

Columbia’s discourse of “reimagining” the community in Manhattanville with their Expansion, including saving the neighborhood from blight and “bringing jobs,” undercuts the fact that their Expansion displaced many businesses and people, discounted the Community Board’s designs for the neighborhood based on what the community wanted, and reenacts earlier forms of urban renewal as well as securitization. Their perception is one of coming to save the neighborhood and revitalize it, without taking into account how it negatively impacts residents, or at least does not benefit them in a way a mixed-used development might have. Residents of Grant Houses have taken the microphone into their own hands, using the Community Benefits Agreement funding, to express their view of community via a recently opened radio station and to show that they are not isolated, but are part of a broader, wide-reaching network of actors. Giving a face to their name, the residents push for recognition and representation amidst toxic narratives and a toxic landscape that tends to value and promote certain forms of knowledge over others.

Isabelle Soifer. 17 February 2020, "Toxic University: Crafting whiteness in West Harlem", Center for Ethnography, Platform for Experimental Collaborative Ethnography, last modified 26 March 2020, accessed 23 February 2025. http://centerforethnography.org/content/toxic-university-crafting-whiteness-west-harlem